Early Detection of Neonatal Infection in NICU Using Machine Learning Models: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study

Abstract

Introduction

Neonatal infections remain a major threat in intensive care units (ICUs), often progressing rapidly and asymptomatically within the first hours of admission. Early detection is critical to improve outcomes, yet timely and reliable risk prediction remains a challenge.

Method

We conducted a retrospective, observational, explainable machine learning cohort study to predict early neonatal infection using high-resolution data from the MIMIC-III database. Two-time windows, 30 and 120 minutes post-ICU admission, were analyzed. Physiological and hematological variables were aggregated, and missing data were imputed using iterative imputation. Multiple classification models were evaluated through stratified five-fold cross-validation, and model interpretability was assessed with feature importance and SHAP analysis.

Result

CatBoost demonstrated the highest performance in the 30-minute window (F1-score = 0.76), while Gradient Boosting achieved the best results in the 120-minute window (F1-score ≈ 0.80). Key predictors included heart rate, white blood cell count, and temperature, reflecting both physiological stability and immune response. Model performance improved with longer observation windows, underscoring the role of data availability in predictive accuracy.

Discussion

A staged deployment, CatBoost at admission followed by Gradient Boosting after 2hours, could balance immediacy and precision. High missing-value rates were manageable with model-based imputation, yet external validation was required, given single-centre data and device heterogeneity.

Conclusion

This study proposes a two-stage decision-support system that adapts to data collected during early and later ICU admission periods. By combining accurate prediction with model interpretability, the framework may enable timely diagnosis and targeted interventions, ultimately reducing neonatal morbidity and mortality.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neonatal infections, including sepsis, remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in newborns, particularly in critical care settings, such as neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [1,2]. These infections, often difficult to diagnose in their early stages, require timely identification to enable effective interventions. Delayed or inaccurate diagnosis can result in rapid disease progression, increased mortality, and long-term complications [3]. In parallel, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has further complicated neonatal infection management, necessitating data-driven approaches to optimize diagnosis and treatment strategies [4].

Traditional scoring systems, such as SNAP-II and CRIB, are widely used to evaluate the severity of neonatal illness and predict outcomes [5], [6]. However, these tools are limited by their reliance on fixed variables and retrospective observations, often spanning 12–24 hours, which delays critical decision-making [6]. Furthermore, they lack the capacity to handle complex, multidimensional datasets or account for dynamic changes in patient conditions [7]. These limitations highlight the need for advanced, real-time predictive tools.

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative approach in healthcare, enabling the integration and analysis of complex data from diverse sources [8]. Leveraging ML and deep learning (DL) models, such as random forests, support vector machines, and recurrent neural networks, enables accurate predictions of neonatal infection onset and associated mortality risks [9], [10]. These models have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional methods, particularly when applied to large datasets, such as MIMIC-III, a publicly available database of critical care patient records [11]. MIMIC-III provides a rich repository of neonatal data, including physiological measurements, laboratory results, and clinical interventions, making it an ideal resource for developing robust predictive models [12].

This thesis aims to develop a machine learning framework using data from MIMIC-III to predict neonatal infections and their associated mortality risks. By focusing on real-time measurement data collected within the critical first hours of care, the proposed approach seeks to enable early, actionable predictions. This framework will incorporate explainable AI methodologies to ensure transparency and trust in the predictive models, facilitating their integration into clinical workflows [13]. The outcomes of this research have the potential to enhance early diagnosis, improve resource allocation, and ultimately reduce neonatal mortality in NICUs.

2. METHOD

2.1. Study Design

This research was conducted as a retrospective observational cohort study using the publicly available MIMIC-III Clinical Database (v1.4). The study aimed to address the research question: Can machine learning models applied within the first 30 and 120 minutes of ICU admission accurately predict neonatal infection?

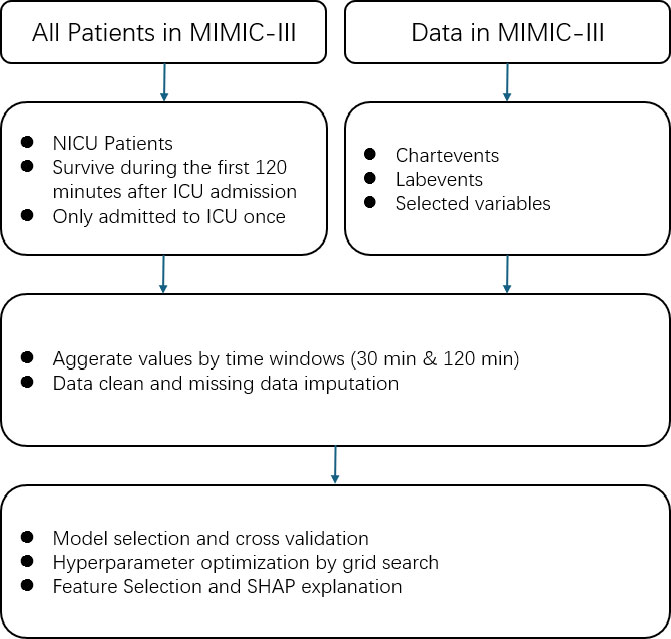

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of the study. A quantitative analytical approach was used. The study population included 6,539 neonates admitted to the NICU, of whom 4,013 were diagnosed with infection. Patients with multiple ICU admissions or those who died within two hours of admission were excluded.

Physiological and hematological variables (e.g., heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, blood pressure, white blood cell counts) were extracted and aggregated into two time windows (30 and 120 minutes post-admission). Data preprocessing included exclusion criteria, variable aggregation, and imputation of missing values.

Proposed approach for infection prediction in NICU.

The study was observational and non-experimental, based on secondary analysis of de-identified clinical data. Multiple supervised machine learning algorithms were evaluated, and performance was assessed using stratified five-fold cross-validation, with F1-score as the primary metric.

2.2. Data Resource

The data source for this retrospective observational study was the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III (MIMIC-III), a relational critical care database developed by the MIT Lab for Computational Physiology. MIMIC-III is a publicly available dataset containing de-identified health data from patients admitted to critical care units at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. It contains detailed health-related data for 46,520 unique critical care patients admitted between 2001 and 2013, covering 58,976 hospital admissions and 38597 ICU stays. The dataset included demographics, clinical diagnoses, procedures, medications, lab results, and other data. MIMIC-III contains over 2 million chart events, 380,000 laboratory measurements, and over 10,000 procedures, making it a comprehensive dataset for critical care research.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

After data collection, preprocessing is crucial for achieving reliable, complete, and high-quality data for prediction tasks [14], [15]. In this research, preprocessing includes collecting relevant data and handling missing values.

This research aimed to develop a machine learning model to predict newborn infections within a short time frame. The first step involved gathering data from patients in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), who were the target population. We excluded patients who had been admitted to the ICU more than once, as well as those who died within two hours of ICU admission, in order to reduce model complexity [12]. Ultimately, we selected 6,539 infants from the NICU cohort, of whom 4,013 were infected.

In the coding section, we extracted data on patients from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) within the MIMIC-III v1.4 database using the following criteria. First, we included only admissions in which the first care unit was recorded as NICU. To ensure adequate observation time, patients were excluded if they died within 120 minutes of ICU admission; those who survived beyond 120 minutes or who did not die during hospitalization were retained. To avoid duplicate information and reduce confounding, we further excluded patients with multiple NICU stays, retaining only those with a single NICU admission. After applying these criteria, demographic information, including gender, was obtained from the patients' table, and additional clinical and administrative details (e.g., admission time, discharge status, ethnicity, religion) were linked through the admissions table.

Various physiological and hematological parameters are essential for early identification and management in predicting neonatal infections. Heart rate is a key indicator; tachycardia may signal systemic infections or sepsis, while bradycardia can indicate severe infection. Respiratory rate is also crucial, with tachypnea reflecting respiratory distress and decreased rates indicating failure [16]. Oxygen saturation (SaO2) levels reflect respiratory efficiency, particularly during infections, such as pneumonia [17]. Temperature regulation is vital, as fever or hypothermia indicates systemic responses to infection. Elevated temperatures suggest inflammation, and hypothermia often indicates severe sepsis. Blood pressure readings are important for assessing [18] cardiovascular stability, with hypotension being a critical late sign of septic shock [19]. Hematological markers are indispensable; white blood cell counts can indicate infection, while neutrophil counts reflect acute bacterial responses. Lymphocyte counts may decrease, signifying immunosuppression. Thrombocytopenia and abnormal hemoglobin levels may complicate infection management [20]. Immature granulocytes in blood smears indicate a strong bone marrow response to severe infections [16].

Not all measurements were collected simultaneously for each patient, and some measurements were taken multiple times. We aggregated the data for each patient into two time windows: 30 minutes and 120 minutes. For the 30-minute dataset, we calculated the minimum, maximum, and mean values for each variable within the first 30 minutes after patients were admitted to the ICU. We then applied the same aggregation process to the 120-minute dataset.

2.4. Missing Value Imputation

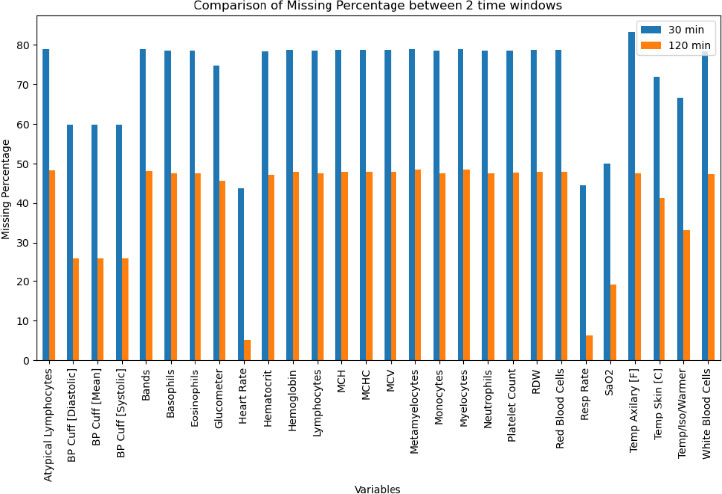

In a hospital environment, particularly in ICUs, many variables are measured. However, these measurements are not always collected and available simultaneously for each patient, leading to the common issue of missing data, especially during the early hours of admission. Fig. 2 illustrates the percentage of missing data in the raw dataset, highlighting that handling missing values is a critical challenge. Proper management of missing data is essential to ensure the validity and generalizability of study findings [21], [22].

There are three types of missing data: Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), and Missing Not at Random (MNAR). Understanding these data types is essential for determining whether imputation methods, sensitivity analyses, or model adjustments are needed to avoid drawing misleading conclusions from research findings [23].

We explored the nature of missingness using a multi-step approach. First, we employed Missingno visualizations, a matrix plot to reveal patterns of missing data across observations and variables, and a heatmap to identify correlations in missingness [24]. Next, we performed Little’s MCAR test by label encoding categorical variables and applying mean imputation to create a complete covariance matrix. We compared this matrix with that of the fully observed subset and used the resulting statistics to determine whether the data were missing completely at random (MCAR). A non-significant p-value (above 0.05) supported the MCAR hypothesis, while a significant result indicated that the data might follow missing at random (MAR) or missing not at random (MNAR) mechanisms [25]. To differentiate between MAR and MNAR, we conducted chi-square tests for each variable with missing data, creating a binary indicator to evaluate associations with other observed variables; significant results suggested MAR [26]. Finally, we performed two-sample t-tests to determine if observed values differed between the “missing” and “non-missing” groups for each variable. A significant difference (p < 0.05) suggested that missingness could be MNAR, implying dependence on unobserved information rather than solely on observed data.

We examined two strategies for addressing missing data, row removal based on a pre-defined missing threshold (θ) and three imputation methods (Simple Imputer, KNN Imputer, and Iterative Imputer) [27], [28]. We systematically varied θ from 0.95 to 0.6 in increments of 0.05, discarding rows that surpassed each threshold’s proportion of missing values to ensure that highly incomplete rows did not compromise imputation results. Subsequently, we artificially masked 10% of the numeric entries to create a known “ground truth” for performance evaluation, comparing original values to the imputed ones.

We assessed imputation quality using mean squared error (MSE) and mean absolute error (MAE), calculated over all features where masking occurred. Hyperparameters, such as k-values for KNN and iteration counts for the iterative imputer, were tuned via grid search, providing a robust benchmark of each method’s effectiveness. By systematically quantifying the trade-offs between excluding rows and employing various imputation techniques, this approach provides a clearer understanding of optimal strategies for handling incomplete datasets.

2.5. Model Selection

We explored a diverse range of classification algorithms to capture a broad spectrum of decision boundaries, incorporating models from multiple learning paradigms, such as Linear and Statistical Models (Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes), Tree-Based Methods (Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, Extra Trees, CatBoost, HistGradientBoosting, and Bagging Classifier), Instance-Based Learning (k-Nearest Neighbors), Neural Networks (Multilayer Perceptron), and Support Vector Machine [29].

Data missing percentage of raw datasets.

This comprehensive set of models ensured that both linear and non-linear decision boundaries were considered, allowing for a more robust evaluation of classification performance.

To ensure a reliable assessment of model generalizability, we adopted a Stratified K-Fold cross-validation approach with five folds (n_splits = 5). This technique maintains consistency in class distribution across folds, mitigating potential class imbalance and ensuring fair evaluation across all candidate models [30].

Each model's predictive performance was assessed using four key metrics, computed through cross-validation:

• Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified instances.

• Precision (weighted): The class-weighted mean of precision across all categories.

• Recall (weighted): The class-weighted means of recall, ensuring balanced sensitivity.

• F1-Score (weighted): The harmonic means of precision and recall, providing a robust measure of model effectiveness.

The mean scores for each metric were computed across all five folds to ensure stable performance evaluation.

The best-performing model was determined based on its mean F1-score, as this metric provides a balanced evaluation of both precision and recall, making it particularly suitable for imbalanced datasets [31]. Once the top-performing model was identified, it was retrained on the entire imputed dataset (X_imputed, y) to produce a final, optimized predictive model ready for validation and deployment.

2.6. Hyperparameter Optimization

We rigorously evaluated a diverse set of algorithms by employing this multi-step framework, comprising imputation, cross-validation, and metric-based model selection. This approach ensured that the final chosen model exhibited strong predictive performance across multiple evaluation metrics, enhancing its reliability for real-world applications [32].

A predefined grid of hyperparameter values is established, covering a range of model-specific configurations, such as learning rate, regularization strength, and complexity parameters. The grid systematically enumerates all possible combinations to be tested, ensuring that various configurations are explored comprehensively.

For the evaluation of each hyperparameter combination, a k-fold cross-validation procedure was employed. Specifically, the training data were split into k folds (e.g., k=5), and each fold was treated as a temporary validation set, while the remaining folds were used for model training. Five-fold offered the best trade-off between statistical reliability and computation cost. Performance metrics, such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, were computed on the validation fold, and the process was repeated for each parameter combination. This approach mitigated the risk of overfitting to a single train–validation partition and provided more robust estimates of out-of-sample performance [33].

All hyperparameter combinations in the predefined grid were iterated over, with each model built and evaluated using the cross-validation scheme described above. For GradientBoosting, the grid spanned n_estimators (50, 100, 150), learning_rate (0.01, 0.05, 0.1), max_depth (3, 5, 7), and subsample (0.6, 0.8, 1) to balance ensemble size, step size, tree complexity, and sampling noise. For CatBoost, we varied iterations (100, 200, 300), learning_rate (0.01, 0.05, 0.1), depth (4, 6, 8), l2_leaf_reg (1, 3, 5), and border count (32, 64, 128), allowing fine-grained control over boosting rounds, tree depth, regularization strength, and stochasticity. The mean (optionally standard deviation) of the performance metrics across folds was recorded for each parameter setting. Computational parallelization (using multiple CPU cores or threads; CPU: AMD Ryzen 9 3900X) was leveraged where feasible to expedite the search process. The configuration achieving the highest mean performance metric (e.g., the highest mean F1-score) was identified as optimal. In certain cases, a secondary performance measure (e.g., model complexity or runtime) or a tiebreaker (e.g., validation loss) was used to distinguish between comparably performing solutions.

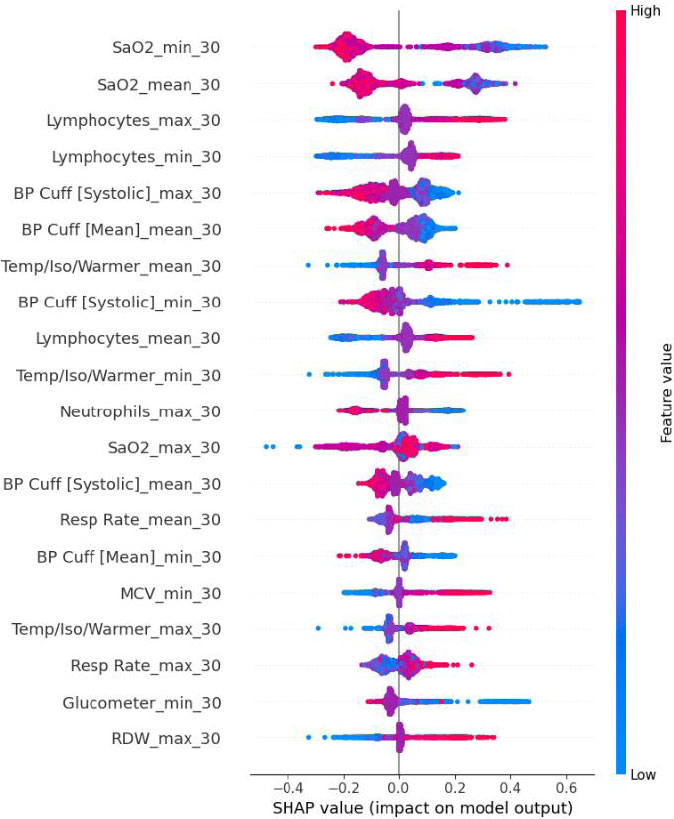

2.7. Feature Selection

The selected model’s built-in feature importance mechanism was first used to assign each variable a numerical score reflecting its contribution to predictive accuracy. The full feature matrix was used to train baseline tree-based ensembles, including Random Forest, Extra Trees, Gradient Boosting, HistGradient Boosting, LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost. The native importance metric of each model, mean decrease in impurity for bagging trees and total gain for boosting algorithms, was then extracted. These scores were min-max scaled to 0–1 and averaged to create a consensus ranking that highlighted variables deemed influential across models. We then generated a ranked list of variables in descending order of importance. Subsequently, we employed the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework to quantify each feature’s contribution to individual predictions, producing both summary plots and class-level insights. This interpretability analysis helped clarify which variables most strongly influenced the model’s predictive outcomes.

To further investigate the relationship between feature subset size and model performance, we adopted an incremental coverage scheme ranging from 10% to 80% (in 5% increments). Specifically, if there were F total features, a coverage level of c% dictated retaining the top [c%×F] features according to the importance ranking. For example, 10% coverage preserved only the top 10% of features, whereas 80% coverage retained 80% of the most important ones. At each coverage level, we trained a new CatBoost model (using the same hyperparameters) and conducted a 5-fold stratified cross-validation. The mean and standard deviation of accuracy for each subset provided insight into both performance and stability across different feature inclusion thresholds.

3. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 presents the final list of 23 selected variables. In the 30-minute dataset, several variables exhibited notably high missingness rates (e.g., atypical lymphocytes, bands, basophils, and other hematological markers often missing in over 70% of cases), while respiratory- and temperature-related features (e.g., heart rate, resp rate, temp skin) showed comparatively lower missingness (40–70%). Overall, most mean values differed between the infected and non-infected groups in the 30-minute window, with parameters, such as heart rate, neutrophils, and white blood cells, tending to be higher in the infected cohort. By contrast, the 120-minute dataset contained fewer missing observations across many features (most falling in the 20–50% range) and maintained a similar pattern of differences between infected and non-infected groups (e.g., higher heart rate and lower neutrophils among infected). Although the mean values of several variables (e.g., basophils, monocytes) remained comparable across groups, both time windows demonstrated consistent distinctions in key physiological and hematologic parameters between infected and non-infected neonates.

After conducting Little’s MCAR test, the p-value for both the 30-minute and 120-minute datasets was less than 0.001, indicating that the missing data were not completely random. Next, we evaluated the importance of each variable using random forest accuracy, and the results showed that all variables had high accuracy (mean = 0.99).

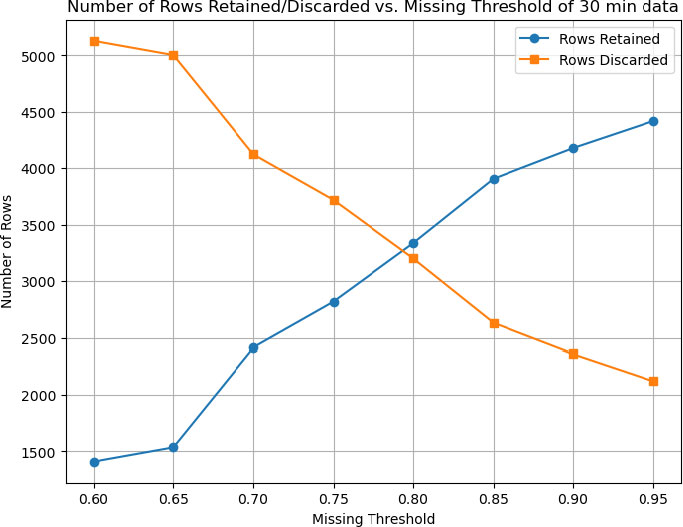

3.1. Row Removal Threshold Result

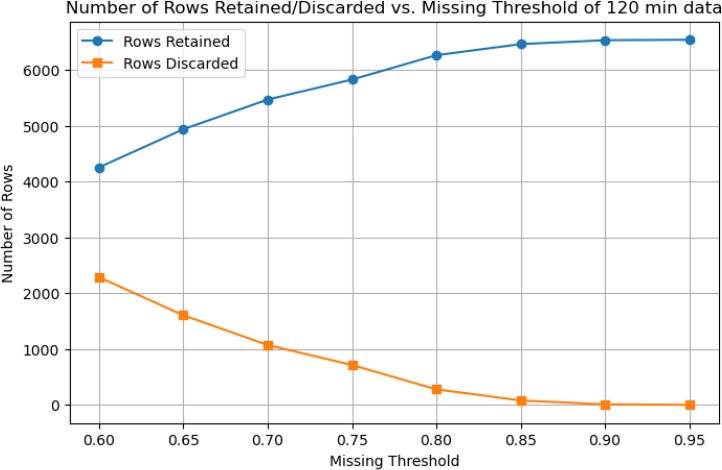

Figure 1 illustrates how varying the missingness threshold (0.60≤θ≤0.95) affects the number of retained and discarded rows in the 30-minute and 120-minute datasets, respectively. As the threshold becomes more permissive (increasing from 0.60 to 0.95), the number of retained and discarded rows changes as follows:

• 30-Minute Data: At the lowest threshold (0.60), only about 1,500 rows are retained, while approximately 5,000 rows are discarded, indicating that many rows exceed 60% missingness. As the threshold increases, the strict row-removal criteria are relaxed, allowing more rows to remain in the dataset. By a threshold of 0.95, nearly 6,500 rows are retained and fewer than 500 are excluded (Fig. 3).

• 120-Minute Data: A similar trend is observed, although even at θ = 0.60, a larger portion of rows (over 4,000) is retained compared to the 30-minute dataset. This suggests that the 120-minute dataset contains fewer high-missingness rows or generally more complete measurements. By θ = 0.95, over 6,300 rows are retained, and only a small fraction are removed (Fig. 4).

Overall, these results demonstrate that raising the missingness threshold substantially increases the number of retained samples, especially for the 30-minute data (which generally exhibit higher missing rates). Investigators must balance the desire to retain more data with the risk that overly incomplete records may introduce noise or degrade imputation quality.

3.2. Best Imputation Method

To identify the optimal approach to handling missing data in both the 30-minute and 120-minute datasets, we systematically varied the row-removal threshold, defined as the maximum allowable proportion of missing features per row, and compared multiple imputation strategies. Performance was assessed using mean squared error (MSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) relative to a “ground truth” created by artificially masking 10% of the values. For the 120-minute dataset, a threshold of 95% missingness discarded only eight rows while yielding the lowest MSE (968,311) and MAE (91.65) under Iterative Imputer (max_iter=12), demonstrating that even highly incomplete rows could be retained without severely compromising imputation accuracy. By contrast, the 30-minute data benefited from a more stringent threshold of 75%, removing 3,720 rows, to achieve the lowest MSE (962,903) and MAE (91.42) with the same imputation method. Despite differing optimal thresholds, Iterative Imputer consistently outperformed simpler approaches in both time windows, underscoring the utility of modeling inter-variable relationships to achieve robust imputation results.

3.3. Best Machine Learning Model

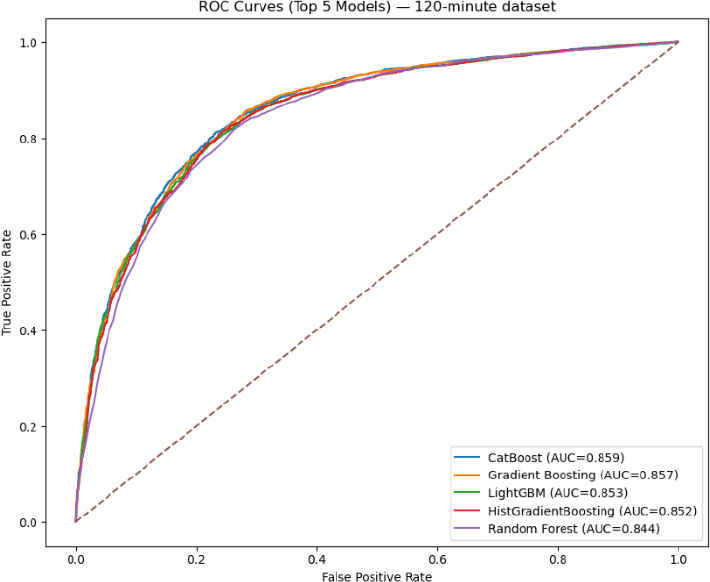

After applying the various classification algorithms to the 120-minute dataset, as shown in Fig. (5), Gradient Boosting emerged as the top performer, achieving the highest average F1-score (0.7983) across the cross-validation folds. In terms of overall classification metrics, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1, Gradient Boosting consistently outperformed established ensemble methods, such as Random Forest and CatBoost, as well as linear/logistic models (e.g., Logistic Regression) and instance-based methods (KNN). This result indicates that, over a longer 120-minute window of recorded physiological and laboratory parameters, a boosted ensemble approach can successfully capture complex nonlinear patterns that distinguish infected from non-infected neonates.

Proposed approach for infection prediction in nicu of 30-minute data set.

Proposed approach for infection prediction in nicu of 120-minute data set.

ROC for the top five models for the 120-minute dataset.

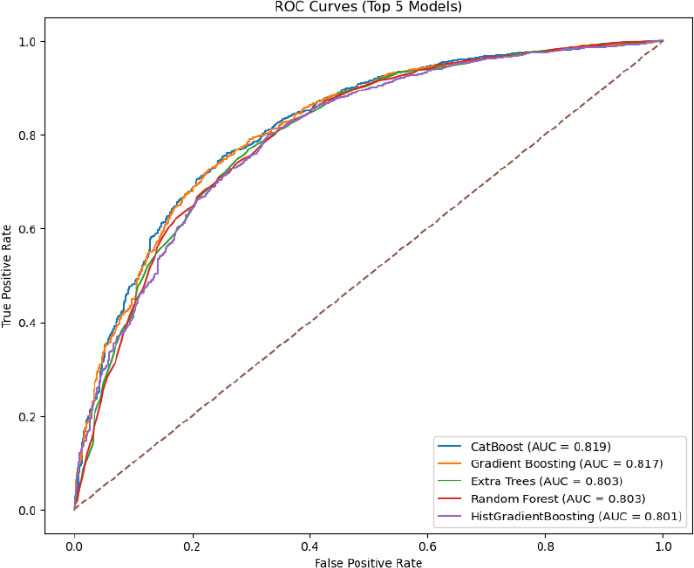

In contrast, (Fig. 6) shows that CatBoost was the best-performing algorithm on the 30-minute data based on F1-score (0.7634), narrowly surpassing Gradient Boosting (0.7628) and other tree-based methods (e.g., Random Forest, LightGBM) in terms of balanced predictive performance. Although some algorithms (e.g., Logistic Regression) also demonstrated robust accuracy, CatBoost’s specialized handling of categorical features and iterative boosting resulted in more balanced gains in precision and recall, making it particularly effective in this shorter time window, where missing data and limited observation periods can constrain model inputs.

Notably, the F1-scores for Gradient Boosting (on the 120-minute data) and CatBoost (on the 30-minute data) were sufficiently close that either method could be considered a strong candidate for modeling neonatal infection risk. Consequently, the next stage of experimentation applied both CatBoost and Gradient Boosting to both time windows with more targeted hyperparameter optimization, ensuring that the final model selection reflects the nuances of each approach’s performance in different temporal contexts. This two-model strategy aims to determine which boosting framework ultimately provides the most consistent and clinically relevant predictions.

We conducted an extensive grid search to optimize CatBoost and Gradient Boosting models for both the 30-minute and 120-minute datasets. Each experiment varied key parameters, such as tree depth, number of iterations (or estimators), learning rate, and subsampling rates, with cross-validation (CV) accuracy serving as the primary criterion for ranking configurations. For the 30-minute dataset, CatBoost achieved the highest CV accuracy (approximately 0.7946) with a moderate tree depth (depth=4) and 300 iterations, at a learning rate of 0.05. By contrast, the best Gradient Boosting model on the same dataset achieved a CV accuracy of 0.7903, reflecting competitive but slightly lower performance than CatBoost. Inspection of confusion matrices and classification reports confirmed that these top-ranked parameter sets offered balanced improvements in both Recall and Precision.

In the 120-minute setting, the situation was reversed; Gradient Boosting attained a marginally higher CV accuracy (about 0.8024) (Fig. 6), surpassing CatBoost’s best of approximately 0.8006. Notably, the optimal Gradient Boosting configuration differed from the 30-minute scenario; it favored a shallower tree (max_depth=3), more estimators (150), and a subsampling rate of 0.8, resulting in consistent gains in predictive performance across folds. Although both models yielded robust accuracy on the fully trained dataset (ranging from 0.82 to 0.86 when evaluated using confusion matrices), the slight discrepancy between the final accuracy and the CV ranking underscores the importance of cross-validation in guiding hyperparameter selection. In particular, the alignment of strong CV scores with high out-of-sample accuracy highlights the capacity of boosted ensemble methods to capture subtle nonlinearities and interactions within newborn infection data, even under demanding early-time-window conditions.

ROC for the top five models for the 30-minute dataset.

3.4. Incremental Coverage Analysis

To evaluate how classification performance is influenced by the number of features retained, we performed an incremental coverage analysis, retaining only the top-ranked features (by model-specific importance) in successive subsets. For the 30-minute dataset (using CatBoost), coverage levels ranged from 10% to 80% of the total feature set, with each subset evaluated via 10-fold cross-validation. As shown in the results table, the highest mean accuracy (0.7896) was achieved at 50% coverage, suggesting that roughly half of the most important features were sufficient to obtain robust predictive performance. Notably, while lower coverage (e.g., 10% or 25%) produced a slightly lower accuracy (0.7754 and 0.7815, respectively), including too many features at 75–80% coverage again lowered accuracy, likely due to the introduction of less informative or redundant variables (Fig. 7).

A similar procedure was applied to the 120-minute dataset with a Gradient Boosting model, which was also tested at 10% to 80% coverage. In this case, the peak accuracy (0.8058) occurred at 80% coverage, indicating that a relatively larger proportion of features contributed a meaningful signal in the extended 120-minute window. Despite near-competitive accuracy at 70% coverage (0.8045), the model benefited from retaining a broader set of features, perhaps reflecting the richer data collected over a longer timeframe. Overall, these findings underscore that an optimal balance exists between too few features, which may omit important signals, and too many, which may introduce noise or redundancy. By identifying this “optimal point,” we can streamline model complexity while preserving high predictive performance. Table 2 presents a statistical summary of all variables across the two datasets, along with their respective missing rates.

| 30-Minute Dataset | 120-Minute Dataset | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Not infected, mean (std) | Infected, mean (std) | Total, mean (std) | Missing rate (%) | Not infected, mean (std) | Infected, mean (std) | Total, mean (std) | Missing rate (%) |

| Atypical Lymphocytes | 0.80 (1.64) | 1.33 (2.66) | 1.12 (2.32) | 78.84 | 0.79 (1.59) | 1.25 (2.47) | 1.03 (2.10) | 48.20 |

| BP Cuff [Diastolic] | 37.62 (8.16) | 33.60 (18.58) | 34.77 (16.35) | 59.78 | 37.64 (7.64) | 33.41 (14.89) | 34.97 (12.86) | 25.71 |

| BP Cuff [Mean] | 49.59 (8.24) | 43.75 (8.83) | 45.45 (9.06) | 59.78 | 49.77 (7.61) | 43.85 (7.80) | 46.04 (8.24) | 25.77 |

| BP Cuff [Systolic] | 68.97 (9.64) | 62.06 (16.46) | 64.07 (15.13) | 59.78 | 69.34 (8.99) | 61.99 (10.40) | 64.71 (10.52) | 25.72 |

| Bands | 2.54 (3.63) | 1.49 (3.00) | 1.91 (3.30) | 78.83 | 2.59 (3.79) | 1.72 (3.20) | 2.15 (3.52) | 48.16 |

| Basophils | 0.28 (0.60) | 0.23 (0.50) | 0.25 (0.54) | 78.54 | 0.24 (0.54) | 0.23 (0.51) | 0.24 (0.52) | 47.56 |

| Eosinophils | 2.16 (2.25) | 2.29 (2.34) | 2.24 (2.31) | 78.54 | 1.99 (1.99) | 2.24 (2.25) | 2.12 (2.13) | 47.56 |

| Glucometer | 67.60 (20.57) | 63.13 (25.64) | 64.18 (24.60) | 74.77 | 69.11 (19.12) | 69.55 (25.23) | 69.43 (23.77) | 45.70 |

| Heart Rate | 143.93 (16.58) | 149.90 (17.15) | 148.15 (17.20) | 43.71 | 141.23 (15.17) | 146.93 (15.39) | 144.83 (15.55) | 5.12 |

| Hematocrit | 51.67 (5.72) | 48.93 (6.65) | 50.04 (6.43) | 78.35 | 51.81 (5.71) | 49.03 (6.83) | 50.38 (6.46) | 47.13 |

| Hemoglobin | 17.44 (1.93) | 16.32 (2.16) | 16.78 (2.14) | 78.65 | 17.50 (1.92) | 16.38 (2.25) | 16.92 (2.17) | 47.82 |

| Lymphocytes | 30.40 (13.73) | 49.31 (19.32) | 41.69 (19.62) | 78.54 | 28.22 (12.17) | 46.79 (19.92) | 37.79 (19.03) | 47.56 |

| MCH | 35.56 (1.94) | 36.59 (2.61) | 36.17 (2.41) | 78.65 | 35.56 (1.89) | 36.74 (2.46) | 36.17 (2.28) | 47.82 |

| MCHC | 33.76 (0.94) | 33.36 (1.09) | 33.52 (1.05) | 78.67 | 33.78 (0.91) | 33.45 (1.06) | 33.61 (1.00) | 47.86 |

| MCV | 105.39 (5.27) | 109.80 (8.17) | 108.01 (7.45) | 78.67 | 105.36 (5.31) | 109.96 (7.71) | 107.72 (7.04) | 47.86 |

| Metamyelocytes | 0.25 (0.68) | 0.22 (0.78) | 0.23 (0.74) | 78.90 | 0.27 (0.70) | 0.21 (0.72) | 0.24 (0.71) | 48.47 |

| Monocytes | 6.87 (3.73) | 6.78 (3.65) | 6.82 (3.68) | 78.54 | 7.11 (3.63) | 6.91 (3.82) | 7.01 (3.73) | 47.56 |

| Myelocytes | 0.15 (0.68) | 0.12 (0.55) | 0.13 (0.60) | 78.96 | 0.14 (0.56) | 0.12 (0.52) | 0.13 (0.54) | 48.48 |

| Neutrophils | 56.59 (14.78) | 38.07 (18.80) | 45.53 (19.53) | 78.54 | 58.66 (13.49) | 40.41 (19.34) | 49.26 (19.08) | 47.56 |

| Platelet Count | 307.43 (73.73) | 275.28 (80.91) | 288.21 (79.65) | 78.64 | 301.87 (78.21) | 265.36 (81.77) | 283.00 (82.11) | 47.68 |

| RDW | 16.62 (0.97) | 17.17 (1.41) | 16.95 (1.28) | 78.68 | 16.65 (1.01) | 17.13 (1.37) | 16.90 (1.23) | 47.94 |

| Red Blood Cells | 4.92 (0.59) | 4.48 (0.71) | 4.65 (0.70) | 78.67 | 4.93 (0.57) | 4.47 (0.70) | 4.70 (0.68) | 47.86 |

| Resp Rate | 49.70 (13.33) | 51.90 (14.84) | 51.25 (14.44) | 44.55 | 48.11 (11.37) | 52.17 (12.84) | 50.66 (12.47) | 6.29 |

| SaO2 | 97.48 (5.04) | 96.00 (4.49) | 96.35 (4.67) | 49.92 | 97.85 (3.92) | 96.33 (3.16) | 96.77 (3.47) | 19.10 |

| Temp Axilary [F] | 98.41 (0.70) | 98.51 (0.83) | 98.49 (0.80) | 83.25 | 98.52 (0.61) | 98.71 (0.71) | 98.66 (0.69) | 47.51 |

| Temp Skin [C] | 36.60 (4.77) | 36.57 (3.94) | 36.57 (4.10) | 71.92 | 36.53 (3.94) | 36.58 (3.72) | 36.57 (3.77) | 41.33 |

| Temp/Iso/Warmer | 35.95 (3.02) | 36.27 (1.84) | 36.20 (2.15) | 66.63 | 35.87 (3.05) | 36.13 (2.36) | 36.06 (2.55) | 33.15 |

| White Blood Cells | 17.06 (5.57) | 13.00 (6.01) | 14.64 (6.16) | 78.42 | 17.27 (5.47) | 13.02 (6.54) | 15.08 (6.41) | 47.32 |

SHAP value for the 30-minute dataset of CatBoost.

4. LIMITATIONS

This study includes several limitations. The first one is data quality and heterogeneity. Although we used standardized ICU data from MIMIC-III, variations in measurement frequency, device calibration, and charting practices can introduce biases. The real-world deployment of our model, especially in other institutions, would require local calibration and external validation. In this study, we explored multiple machine learning–based methods for predicting neonatal infection risk and compared their performances with a more conventional reference scoring system. Specifically, we aimed to identify an algorithm that could accurately predict infection-related outcomes when data are aggregated from the first 30 or 120 minutes of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Our findings revealed notable differences in the models’ performances across these two time windows, highlighting the trade-offs of each approach for real-world clinical use.

We only extracted variables from the first 30 or 120 minutes. Future work could incorporate dynamic, time-series features beyond these discrete windows or investigate sliding-window updates (e.g., every 15 minutes) to capture evolving physiologic patterns.

Although CatBoost and Gradient Boosting can produce feature-importance estimates or SHAP values, the underlying mechanisms remain “black-box” at the bedside. Efforts to embed transparent, clinically interpretable frameworks (e.g., rule-based ensembles) might further facilitate end-user adoption.

To ensure transportability across hospital systems, future work should conduct external validation using leave-one-hospital-out and temporal designs, and, where feasible, a short prospective “shadow” deployment at new sites. Before testing, ontologies and units should be harmonized, device and charting differences aligned, and preprocessing steps (imputation and standardization) locked on the training sites only, then applied unchanged to held-out sites to prevent data leakage. Site-specific and pooled (random-effects) AUROC and AUPRC, as well as calibration metrics (intercept, slope, Brier score), should be reported. Global thresholds should be compared with site-specific thresholds using lightweight local recalibration methods, such as intercept-only adjustment, Platt scaling, or isotonic regression. When data cannot leave an institution, privacy-preserving or federated evaluation should be used, employing secure aggregation that returns only metrics and plots.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored multiple machine learning–based methods for predicting neonatal infection risk and compared their performances with a more conventional reference scoring system. Specifically, we aimed to identify an algorithm that could accurately predict infection-related outcomes when data are aggregated from the first 30 or 120 minutes of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Our findings revealed notable differences in the models’ performances across these two time windows, highlighting the trade-offs of each approach for real-world clinical use.

Overview of Findings

In the 30-minute dataset, CatBoost emerged as the top-performing model, achieving the highest F1-score (~0.7634) and surpassing Gradient Boosting (~0.7628) and other tree-based and linear methods. The marginal gap between CatBoost and Gradient Boosting suggests that, when data are relatively sparse (i.e., at only 30 minutes into an ICU stay), subtle differences in how ensemble algorithms handle missingness, outlier measurements, and imputation steps can substantially shape final performance metrics. CatBoost’s specialized handling of categorical data, alongside robust boosting iterations, may have conferred an advantage in the “ultra-early” context, where variable availability is inconsistent, and the physiologic signals can be less stable.

When the time window was extended to 120 minutes, Gradient Boosting models exhibited the highest average F1-score (~0.7983) and displayed excellent calibration. This improvement likely stems from the greater data richness at 120 minutes: additional laboratory results, updated vital signs, and more time for hemodynamic fluctuations can allow gradient-boosted ensembles to better capture complex, nonlinear relationships. Nonetheless, CatBoost, Random Forest, and certain neural network models also demonstrated strong discriminatory ability (F1-scores typically above 0.76), suggesting that multiple algorithmic families can achieve clinical usefulness once sufficient data become available. The key difference was that Gradient Boosting achieved slightly higher, more consistent cross-validation scores across accuracy, precision, and recall.

Interpretations and Clinical Implications

Our results underscore the importance of time-dependent data availability in infection-risk modeling. While the 30-minute window allows for extremely early intervention, it imposes considerable data limitations, such as fewer blood gas analyses or incomplete laboratory results. As a result, advanced techniques that excel under missing data or can effectively leverage categorical inputs, like CatBoost, may offer a decisive edge in the first 30 minutes.

By contrast, the 120-minute dataset captures a more complete clinical profile; repeated vital-sign measurements, additional laboratory panels, and extended neurological or cardiovascular observations can refine risk estimation. Gradient Boosting’s marginally superior performance in the 120-minute window highlights how ensemble-based approaches can exploit this richer information to model more nuanced interactions among variables.

From a decision-support perspective, these findings suggest a two-stage or adaptive approach: (1) an ultra-early model suitable for the first 30 to 60 minutes of admission, leveraging robust handling of missing data (CatBoost or a similar boosted method), and (2) a refined model (e.g., Gradient Boosting) retrained with updated data around 120 minutes, delivering a more accurate prediction for subsequent critical-care decisions.

Comparison with Existing Literature

Several prior investigations have compared machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, and neural networks) against established clinical scoring systems for sepsis or infection-related mortality. Consistent with those reports, it was found that ensemble-based algorithms offer better calibration and higher F1 Scores than classical logistic regression or basic scoring systems (e.g., APACHE II or simplified risk scores). Notably, the incremental gains are especially relevant in the “intermediate” time frame (1–2 hours), when important physiologic trends start to manifest yet remain absent at baseline.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Z.C. and Z.Q.: Study conception and design, Z.C.: Collection; Z.C.: Analysis and interpretation of results; Z.C.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ICU | = Intensive Care Unit |

| NICU | = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| ML | = Machine Learning |

| SHAP | = SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| MIMIC-III | = Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care III |

| MCAR | = Missing Completely at Random |

| MAR | = Missing at Random |

| MNAR | = Missing Not at Random |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The creation and sharing of MIMIC-III were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC, Boston, MA, USA; Protocol 2001-P-001699/14) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT COUHES, Cambridge, MA, USA; Protocol 0403000206), with a waiver of informed consent.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The MIMIC-III database contains only de-identified data, and the BIDMC and MIT IRBs granted a waiver of informed consent for the database’s creation and sharing; no identifiable patient information or images are published in this manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the MIMIC-III Clinical Database (v1.4), hosted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Laboratory for Computational Physiology. Access is granted to qualified researchers after completion of the required data use agreement and training.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the MIT Laboratory for Computational Physiology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for maintaining and providing access to the MIMIC-III database. The authors would also like to thank colleagues from the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics at Emory University for their valuable discussions and feedback during the preparation of this study.

DISCLOSURE

Part of this article has previously been published in the thesis “Early Detection of Neonatal Infection in NICU Using Machine Learning Models” (Spring 2025, Emory Theses and Dissertations). The thesis is available at: https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/cn69m5672.