HDI Corpus: A Dataset for Named Entity Recognition for In-Context Herb-Drug Interactions

Abstract

Introduction

This article proposes a new dataset for Named Entity Recognition based on PubMed articles and aiming to address the problem of Herb-Drug Interactions. It aims to offer a new dataset for recognizing herb-drug interaction entities, including contextual information.

Background

Machine learning and Deep learning provide users with powerful tools for task automation, but require large quantities of data to perform well. In the field of Natural Language Processing, training Deep Learning models requires the annotation of large corpora of text. While some corpora exist in medical literature, each specific task requires an adapted corpus.

Methods

The dataset was tested using a classical Named Entity Recognition pipeline, as well as new possibilities offered by generative AI.

Results

The dataset proposes annotated sentences of around a hundred articles and covers 15 entities, including herbs, drugs, and pathologies, as well as contextual information, such as cohort composition, patient information, or pharmacological clues.

Discussion

The study demonstrates that this dataset performs comparably to the DDI (Drug-Drug Interaction) corpus — a standard dataset in the drug Named Entity Recognition — for drug recognition, and performs well on most of the entities. Conclusion: We believe this corpus could help diversify pharmacological Named Entity Recognition.

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of medicinal herbs continues to spread in industrialized countries [1]. Herb-Drug Interactions (HDI) are events caused by the pharmacological interaction between a natural health product and a drug. The risk of interaction when Natural Health Products (NHPs) are used concurrently with a medication is well-documented. While these events are unusual, they can lead to serious issues such as contraceptive failure, transplant rejection, or other adverse events, including death [2].

To handle these interactions, health professionals need access to information through scientific literature, where HDIs are described in clinical and pre-clinical studies or case reports. In real practice, however, professionals lack the time to consult these scientific articles while attending to patients. To help them access relevant information, databases are a valuable tool. Yet, these databases need to be frequently updated to remain relevant. The time and money cost of maintaining a database is thus significant, and tools to improve and ease the collection of information are welcome. One of these tools is Natural Language Processing (NLP) [3].

NLP is a field of informatics and linguistics that aims to process natural language, i.e., human-readable language. It consists of multiple tasks, such as Named Entity Recognition, which aims to extract words or chunks of words corresponding to a given label, Question Answering, and Text Summarization. With the help of NLP, the process of structuring information from unstructured data — in this case, scientific literature — can be greatly improved.

A significant amount of effort is put into structuring data to improve its accessibility and reduce the time spent on unnecessary information. Structured formats, such as JSON, XML, or forms, are different tools used to reach this goal — with varying levels of success [4-6]. Yet, most information is only available as unstructured or semi-structured data.

To automate the shift from unstructured text to structured formats, the ability to find relevant information and categorize it is required. This task might seem trivial at first sight, but it requires both expert knowledge and artificial intelligence tools capable of understanding the context of a sentence.

Successive waves of development in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have led to opportunities to handle this task.

One can cite the advent of Recurrent Neural Networks [7], which greatly improved the integration of context through the model. The next great leap in NLP is the transformer architecture, which led to a whole new set of state-of-the-art models. The attention mechanism used in these architectures, once trained on a given task, allows for an even better consideration of the context and leads to impressive results [8]. The architecture itself, called encoder-decoder, was further modified, leading to encoder-only — with its biggest representative being BERT [9, 10] — and decoder-only models, which formed the basis of, among others, GPT [11, 12]. This model brought us the well-known ChatGPT application.

From there, a shift occurred in NLP methodologies. The traditional methods aim to analyze data to make decisions. For example, one might want to process and classify text into different categories. In the case of information retrieval, one representative example of this approach is the use of Machine Learning models to identify specific entities, such as names of persons, organizations, dates, drugs, etc. This task is called Named Entity Recognition (NER) [13]. In recent years, a groundbreaking change occurred with the birth and democratization of autoregressive language models. The distinctive feature of these models is their ability to generate text to answer queries (often referred to as prompts) submitted by the user [14]. This ability, combined with their impressive ability to adapt to a large variety of situations, makes them an incredible tool in NLP. For instance, while NER aims to find every single entity in a text — leaving users with a second step of information reconstruction — generative models can directly provide structured outputs. Unfortunately, this versatility comes at the cost of huge computational needs and slow training and inference. To run a generative model on consumer hardware, some concessions are needed; the models available in this context are smaller, less efficient, and their context length — which is the length of text they are able to process — is much smaller than their full-size counterparts [15, 16].

Although auto-regressive language models can be used in a wide range of situations, this ease of use must not overshadow analytical methods. The computational time and energy costs of these models might by themselves justify the use of other methods. Furthermore, while the auto-regressive language models are able to solve a wide variety of tasks with little to no training, they do not guarantee better results than specialized analytical models.

One of the major drawbacks of using AI is the need for extensive corpora. These corpora allow models to be trained to handle specific tasks. Thus, the more specific the task, the more specific the corpus needs to be — datasets for biomedical text processing are thus difficult and expensive to constitute. While some datasets exist, such as the DDI Corpus (Drug-Drug Interaction) [17] or the NCBI Disease Dataset [18], they are usually focused on specific tasks or entities, and might not fit a wide range of applications.

In this work, we propose a new dataset, the HDI Corpus, composed of sentences directly extracted from pre-clinical and clinical HDI studies and case reports directly extracted from PubMed Central, the open-access subset from PubMed. This dataset aims to identify entities involved in the description of HDIs. Besides the usual entities highlighted in existing datasets, we also included entities involved in the context of the interactions. As such, besides the ‘Drug,’ ‘Herb,’ and ’Pathology,’ we also included annotations about patient/cohort (’Sex’, ’Age’, ’Size’, etc), dosages, herb preparation process and use.

To evaluate its qualities, we assess this corpus using generative models and their traditional counterparts, and compare it to a widely used pharmacology corpus, the DDI Corpus. We chose to test the ability of auto-regressive language models to extract entities of interest for their straightforward performance evaluation — evaluation metrics being one of the greatest difficulties in generative artificial intelligence evaluation — and their importance in information extraction. Our goal is to provide an overview of their performance, their stability across contexts, and their computational cost. We focus on small models, as these models run on consumer hardware and are thus the most accessible for anyone without access to specialized infrastructure, and for free, increasing their potential in creative uses.

Thus, the following questions are raised:

- How does this new dataset perform on common biomedical NER tasks?

- Given a specific task that could be handled by an analytical model, does a generative model perform better?

- Given the individual performance of generative and analytical models, when should one be preferred over the other?

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Hardware

The models were all tested on a machine with a GeForce RTX 4070 Mobile (8GB VRAM) GPU and an Intel® Core™ i9-13900HX CPU.

2.2. Software

These tests were run using Python. The auto-regressive language models were loaded using Transformers 4.38.1 in a Python 3.11 environment, and Spacy 3.7.4 was used for Named Entity Recognition in a Python 3.12 environment.

Data analysis and visualization were performed using pandas 2.2 and plotly 5.22.

The corresponding configuration files are available on GitHub.

2.3. Datasets

For the Named Entity Recognition (NER) part, the model was trained from scratch using (1) the DDI Corpus, (2) the HDI corpus1.

The DDI Corpus (Drug-Drug Interaction Corpus) is an

Entity-Relation extraction corpus designed in 2013. It is composed of 233 MedLine abstracts and 792 texts from Drugbank, in which 8,502 pharmacological substances and 5028 DDIs are annotated. Although primarily designed for Entity-Relation extraction, the dataset also allows NER due to the presence of annotated substances. The original dataset uses a specific classification and assigns these substances into multiple categories. As these categories are related to deep pharmacological knowledge, we chose to assemble these categories into a single ”drug” category. Once Medline sentences with entities were selected, the dataset consists of 877 sentences for a total of 1836 annotated drugs.

The custom corpus is a corpus we designed specifically for NER and themed around HDI. The corpus contains not only pharmacological substances and herbs, but also elements of context that are important for interpreting interactions. The annotated entities are listed below:

- Drug: Name of a pharmacological substance (INN- International Nonproprietary Name);

- Herb: Name of an herb (scientific or vernacular name) or herbal molecule;

- Herb part: Part of the plant used (leaves, root, etc.);

- Frequency of a treatment or an intervention (3 times a day, ...);

- Extraction process: Preparation method used by the manufacturer or patient to process the plant organ (juice, tea, dried powder, hydro-alcoholic solution such as tincture, maceration, etc.);

- Pathology or absence of healthy volunteers;

- Duration: Duration of a treatment or intervention (for 7 days, ...);

- Study: Description of a study protocol;

- Cohort: Description and composition;

- Age of the individuals involved in the cohort or patient;

- Sex;

- Ethnic group: if described in the description of the cohort

- Target: Pharmacological target (CYP, transporter, efflux pump...);

- Parameter: Biological parameter monitored or modified by a natural active substance

- Amount: Any numerical value;

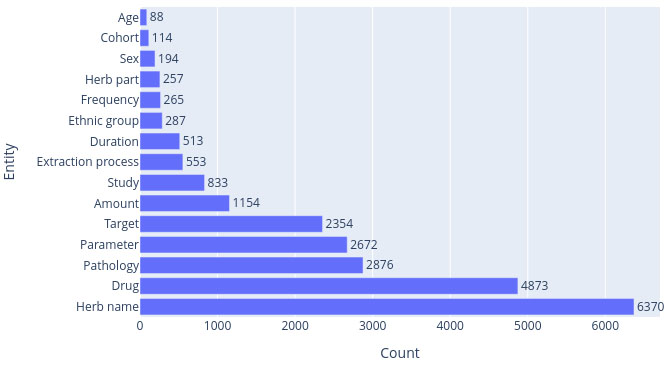

The dataset is composed of 11131 sentences extracted from 95 peer-reviewed articles. Each sentence contains at least one entity, for a total of 23403 annotated entities. A histogram of the number of occurrences per entity is shown in Fig. (1).

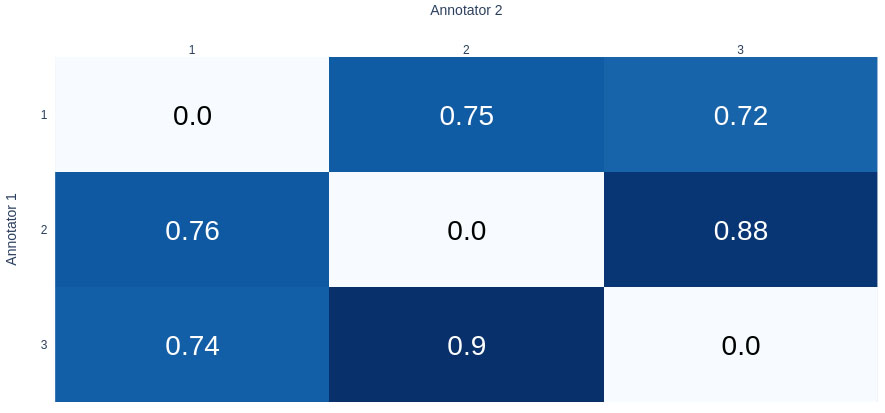

The annotation guide has been redacted, and it is provided in supplementary material. More information about these entities and examples is available there. The dataset was annotated by three different expert annotators, all pharmacists. The annotators were selected among an initial pool of 6 candidates. The selected ones had the best inter-annotator agreement. The inter-annotator agreement, demonstrated in the form of a pairwise mean F1 score over all labels, is shown in Fig. (2).

1 The DDI corpus can be accessed by following the instructions in the related article. Our custom HDI dataset is available on https://github.com/ancnudde/HDIDataset.

Histogram of occurrences by entity.

Inter-annotator agreement between the three selected annotators.

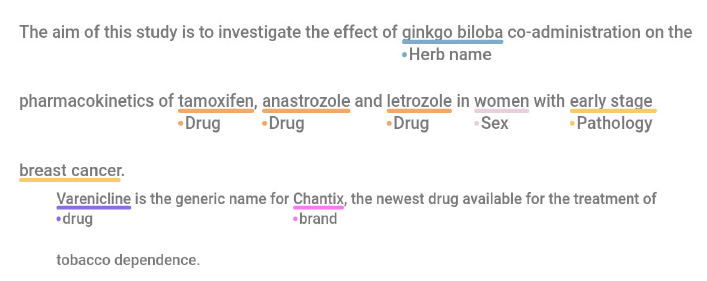

We chose to use the pairwise mean F1 score instead of the more commonly used Kappa metric, as the Kappa score suffers from the lack of definition of what negative examples are. In the case of NER, the ways spans can overlap in a sentence make negative examples uncountable. In this configuration, the Kappa score would poorly tackle token-level annotation particularities, such as span overlaps [19, 20]. Examples of annotations of these two datasets are available in Fig. (3).

Example of annotations for the (a) HDI and (b) DDI corpus. The screenshot is obtained from the Doccano software that was used to annotate the HDI corpus.

3. MODELS

For the NER part of this work, models were trained from scratch using the SpaCy pipeline. The pipeline combines a transformer for text embedding with a conditional random field classifier for classification. The transformer used is BiomedBERT-base-uncased-abstract-fulltext [21], a version of BERT fine-tuned for Biomedical applications. The training was performed using 10-fold cross-validation with different values of learning rate (1.10−5, 5.10−5, 1.10−4, 5.10−4), and performances were tested on an independent test set. Complete training configuration file and splits are available on GitHub.

The value represents the pairwise F1 score between each annotator.

- Example of annotation for the HDI corpus.

- Example of annotation for the DDI corpus.

For the generative part of the work, pretrained models were obtained from HuggingFace. We chose to test various popular models and model sizes, though we were largely limited by our criteria to use consumer-available ones only. The tests were run on Mistral 7B [16] and Phi3 mini (3B) [22], two generalist models. All models were 4-bit quantized.

3.1. Prompting

To reach better performance with text generation, a simple yet powerful tool is prompt engineering. This term encompasses strategies that any user can apply to guide the generation process in order to obtain the desired output. To write better prompts, we divided the input text into multiple parts:

- Context: Gives the context in which the Large Language Model (LLM) is used, for instance, its role (expert, student, etc.). It helps the LLM to use the right tone and vocabulary in its answer.

- Instruction: Explains what the LLM should do given the prompt, i.e., the task to achieve. It guides the LLM to achieve the expected content.

- Output indicator: The expected output format.

- Input: The question or text on which the answer of the LLM will be based.

The prompt was refined iteratively to reach the best performance. We paid specific attention to the output indicator and instruction parts as they seemed to lead to the most important changes in generated text. To get the best answers, we found out the best way was to ask the model to generate a specific format, such as JSON. JSON format has the advantage of linking the attribute to its value in its own structure, helping to fit the generation to user expectations.

A second strategy used in our prompts is the use of few-shot prompting. Few-shot prompting consists of giving the model a small number of examples directly in the prompt to further guide text generation. Few-shot is proven to greatly improve the output of generative language models with little work. A drawback of few-shot learning is the increase in prompt length, leading to longer inference time and saturation of the context size — the number of tokens a model can process. Given the limited size and context length of the models used in this work, we limited the number of shots to 5.

Prompts were also tested with two approaches: the first one aims to identify every type of entity in the same run, the second one divides the general prompt into multiple prompts, one for each entity type. The goal is to assess performance when the model targets a single type of information instead of all at once. The final prompts were obtained after multiple rounds of refining. An example of the final prompt, as well as the naive prompt used as a control, is shown in Table 5.

As the models are supposed to generate JSON, we use a script to parse the output and extract only JSON-compliant content. Any content outside of the correct format, such as comments, is removed in the process.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Named Entity Recognition – NER

Overall performance of the models trained for NER on DDI and HDI corpora is shown in Table 2, and decomposition of results by entity for the HDI corpus in Table 3. While the DDI corpus seems to perform better at first look (F1-score of around 95% for DDI, and around 80% for HDI), a closer look at the detailed scores shows that the performance is highly dependent on the entity. The most represented entities (drugs, herb names, pathology, etc.) yield better scores while the model underperforms for less represented ones (age, cohort, duration, etc.).

There are two notable exceptions with the scores of “parameters” and “extraction process.” This exception is due to the nature of these entities themselves: parameters can actually be targets depending on the context, and the activity of a target can, in some cases, be a parameter. For instance, “CYP2D6” can be considered a target of an interaction, but its activity can be considered a parameter to monitor. The poor performance of the “extraction process” is linked to the difficulty of targeting the right terms in the sentence, as the extraction process is the class that has the widest range of ways it can be expressed. On the contrary, entities like “sex” or “age” are under-represented and still perform well, likely due to their naturally constrained lexical nature [23].

These results show that two parameters are involved in performance: the number of annotations for a given entity, and its lexical complexity.

4.2. Entities Extraction Using Generative Language Models

Results obtained for entity extraction using generative language models are shown in Table 4 for the DDI dataset. The extraction is evaluated on the same dataset as for the NER task. The results for the DDI corpus show the performance of few-shot prompting [24, 25] on the generation of structured data. The difference between the control prompt only and the control prompt with few-shot is significant, outperforming the fine-tuned prompt without few-shot and nearly reaching the scores of a fine-tuned prompt with few-shot. For the HDI corpus, results are shown in Table 5 and 6. Here, the results are much less impressive, especially with Mistral. These observations correspond to those for the traditional named entity recognition task, where the DDI corpus already yields better scores than the HDI corpus. The first source of error lies in the format of the answer given by the model — we only took into account parsable JSON outputs; parsability requires the output to be a valid JSON with the right keys. The fraction of parsable outputs varies from 97% in the best cases (Phi3, few-shot, for “Target” and “Extraction process”) to 0% (Mistral, in multiple cases, including both 0- and few-shot situations).

4.3. Herb-Drug Interaction Dataset Performances

Compared to existing datasets [17, 18, 26], ours provides more types of entities to include context about HDI. Among the 15 entity types, large differences in the trained models’ performance appear. The most represented entities, such as “Drugs”, “Herb names,” or “Pathologies” perform well, while the least represented ones show disappointing results.

Compared to the DDI corpus used as a reference, the HDI corpus performs slightly worse on the “Drug” entity (87.04% vs. 94.51% precision, 90.69% vs. 96.554% recall, and 88.84% vs. 95.5 F1-Score).

| Prompt part | Naive prompt | Naive prompt |

|---|---|---|

| Context Instruction | very word referring to the described entities | Summarize this text. Include information about: drugs, herb name, study, parameter, frequency, herb part, cohort, duration, sex, age, amount, ethnic group, pathology, target, extraction process |

| Output indicator | The following format must be followed: {”DRUGS”: [”List of drugs found in text”]} Please do not add supplementary information. If no information is found for a field, leave the field empty. |

|

| Few-shots* | <s><|user|> This is a scientific article about pharmacology.We need to parse all the cited entities. Find every word referring to the described entities. The following format must be followed:{”DRUGS”: [”List of drugs found in text”]} | |

| Please do not add supplementary in information. If no information is found for a field, leave the field empty. ”Although the precise active components responsible for this anti-diabetic action are unknown, studies with compound K (CK), a final metabolite of protopanaxadiol ginsenoside demonstrate that CK exhibits anti- hyperglycaemic effects through an insulin secreting action similar to metformin.”.<|end|><|assistant|> ”DRUG”: [”metformin”]<|end|><|user|> | ||

| Input | Hypericin, although easily quantifiable, has no antidepressive activity or ability to induce CYP3A4. |

| Model | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDI Corpus | 94.51 | 96.54 | 95.50 |

| HDI Corpus | 80.26 | 79.51 | 79.88 |

| Entity | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | 87.08 | 90.69 | 88.84 |

| Sex | 82.73 | 93.06 | 87.58 |

| Age | 72.91 | 87.50 | 79.55 |

| Herb name | 74.98 | 78.49 | 76.67 |

| Pathology | 70.58 | 74.84 | 72.56 |

| Ethnic group | 70.16 | 64.70 | 67.17 |

| Amount | 65.19 | 63.58 | 64.20 |

| Frequency | 69.71 | 53.12 | 60.11 |

| Herb part | 78.02 | 49.50 | 60.23 |

| Study | 42.14 | 61.68 | 49.73 |

| Duration | 52.35 | 47.08 | 48.69 |

| Target | 63.44 | 68.53 | 65.61 |

| Cohort | 77.86 | 43.65 | 52.92 |

| Parameter | 46.07 | 39.59 | 42.34 |

| Extraction process | 36.84 | 19.78 | 25.60 |

| Prompt | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mistral 7B - control prompt | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mistral 7B - control prompt with few-shots | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| Mistral 7B - fine-tuned prompt | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.60 |

| Mistral 7B - fine-tuned prompt with few-shots | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| Phi3 mini - control prompt | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phi3 mini - control prompt with few-shots | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.73 |

| Phi3 mini - fine-tuned prompt | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.62 |

| Phi3 mini - fine-tuned prompt with few-shots | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| precision | recall | fscore | parsable fraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0 Shot Drug |

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Herb name | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Study | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.59 |

| Parameter | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Frequency | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Herb part | 0.40 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Cohort | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| Duration | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.48 |

| Sex | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.16 | 0.55 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| Amount | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Ethnic group | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Pathology | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| Target | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Extraction process | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

|

Few Shots Drug |

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Herb name | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Study | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.40 |

| Parameter | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Frequency | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Herb part | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0.07 |

| Cohort | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| Duration | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Sex | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Amount | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.28 |

| Ethnic group | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Pathology | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Target | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Extraction process | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.39 |

| precision | recall | fscore | parsable fraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Shot | ||||

| Drug | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Herb name | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.27 |

| Study | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.97 |

| Parameter | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Frequency | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Herb part | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.78 |

| Cohort | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.61 |

| Duration | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.28 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.89 |

| Amount | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Ethnic group | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.83 |

| Pathology | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.99 |

| Target | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.96 |

| Extraction process | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.89 |

| Few Shots | ||||

| Drug | 0.29 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.90 |

| Herb name | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.89 |

| Study | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.81 |

| Parameter | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.96 |

| Frequency | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.81 |

| Herb part | 0.11 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.27 |

| Cohort | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.29 |

| Duration | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.38 |

| Sex | 0.18 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0.56 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.84 |

| Amount | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.67 |

| Ethnic group | 0.12 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 0.90 |

| Pathology | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.58 |

| Target | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.97 |

| Extraction process | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.97 |

| Type of error | Generated | Expected | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing answer | / | 40mg/kg | |

| Knowledge error” | Saline solution | / | Identified as ”DRUG” but not a drug |

| Incorrect format - does not leave empty field | Not specified in the text | / | |

| Missed acronyms | / | HAART | HAART stands for ”Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy” and should be identified as DRUG. Some abbreviations are correctly identified |

| Multiple occurrences of same entities | statins | Statins, statin | To fit the task, doubles are removed from the gold standard, but same entities with different spelling (plural, ...) are not removed and lead to false negatives |

| Abbreviations | ciprofloxacin | ciprofloxacin (CIP) | |

| Annotators errors/debatable choice | venlafaxine | Venlafaxine is a serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor used as an antidepressant | This annotation could be split into multiple ones |

| Multiple references | 4-hydroxy-N- desmethyltamoxifen hydrochloride | 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyltamoxifen hydrochloride/(E/Z)-endoxifen hydrochloride | Same entity described with multiple names in the same sentence |

| Entities confusion | / | Technically correct but in this case, listed under ”DRUG” while ”HERB NAME” is expected | |

| Inflected forms | Clinical studies | Clinical study |

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. Interpretation of NER and Dataset Characteristics

While augmenting the dataset could improve the scores, the under-representation of the problematic fields in the literature makes it hard to apply and would require an expert to analyze text and extract relevant parts, which would be time-consuming and costly. The performance gap between entities is influenced both by frequency and lexical variability. “Targets” and “Parameters” exhibit confusion due to semantic overlaps; targets are defined as enzymes, transporters, or other process elements modulated by interactions, while parameters are elements that can fluctuate and cause clinical events. The resulting ambiguity makes disambiguation particularly difficult [27, 28, 29]. Despite this, both entities are central to article comprehension and should not be excluded.

5.2. Generative Models Error Analysis

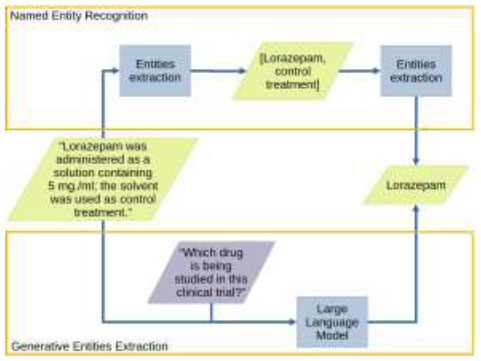

Generative approaches differ from traditional NER, which relies on identifying the exact position of an entity in the text. Generative models can combine recognition and contextual understanding in a single step, helping to prioritize important information directly (Fig. 4). Errors in generative model outputs can be categorized as:

- Format errors: Failure to generate parsable JSON.

- Content errors: Incorrect or missing entities

Table 7 provides examples. The most common are missed entities or mismatches with annotated gold standards. This includes:

- Multiple synonyms in the same sentence

- Abbreviations or acronyms

- Inflected forms

- Semantically correct entities not matching gold annotations

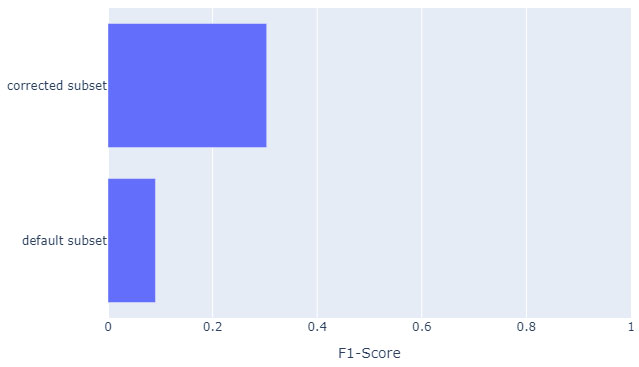

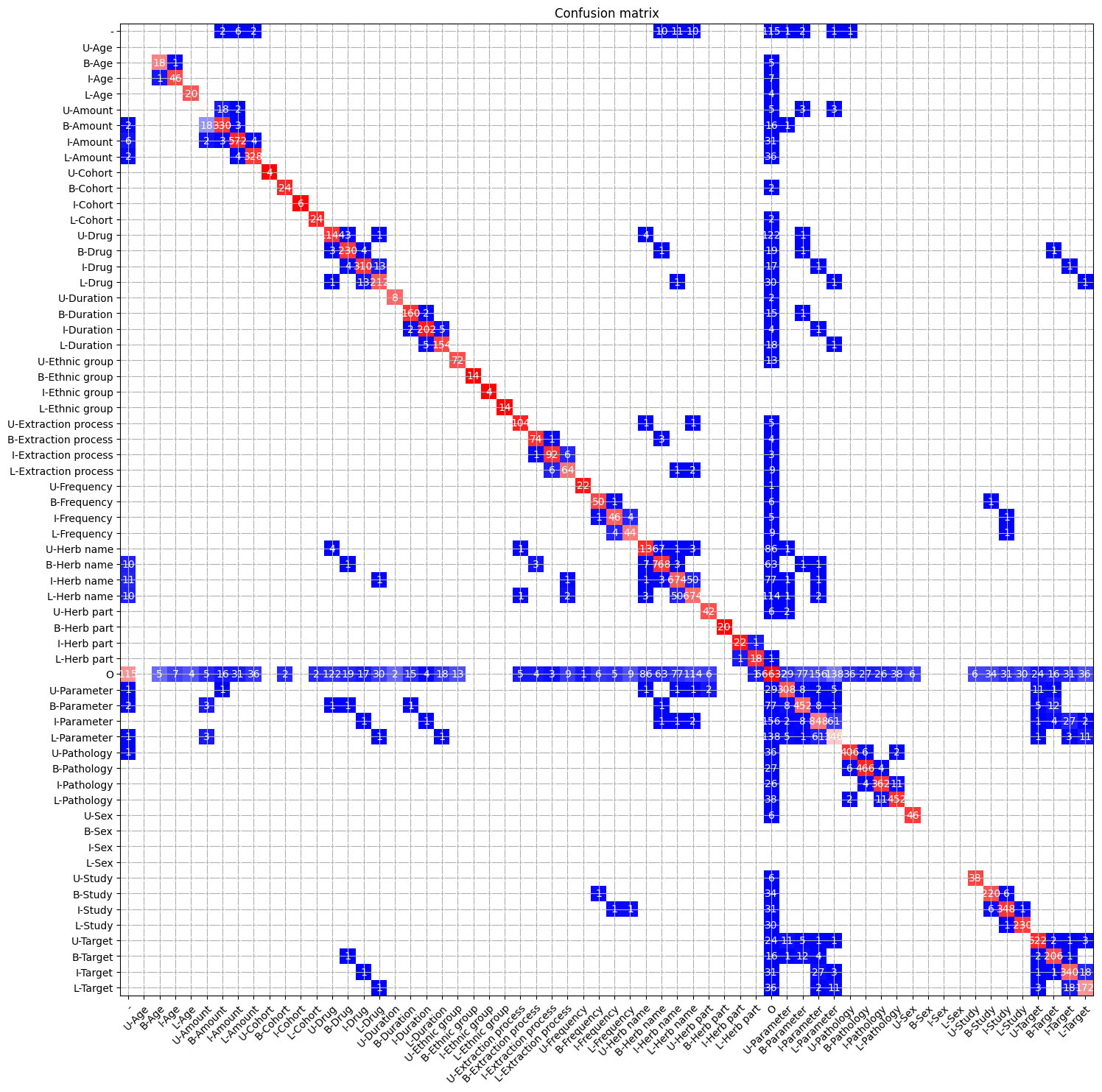

A manually corrected subset of mismatched cases (n = 961) was evaluated to show the frequency and nature of these edge cases (Fig. 5), confusion matrix is shown in Fig. (6). Some errors were also attributable to annotation inconsistencies.

5.3. Generative vs. Traditional Paradigms

The emergence of generative models raises questions about their role compared to traditional approaches [30, 31, 32]. A challenge in evaluating generative outputs lies in the absence of standardized frameworks that handle textual flexibility without expert involvement. Limitations include:

- NER seeks every entity’s exact span; generative models extract meaning, not positions

- Generative models may not reproduce the exact token, spelling, or form used in the reference

Illustration of the difference in named entities extraction between classical NER and Generative Extraction. NER always extracts all recognized entities and thus requires preprocessing to identify the most important entities. Generative Extraction is able to directly identify the most important entities from the prompt context.

Evaluation on a corrected subset composed of sentences containing at least one false positive or false negative generated annotation (n = 961). If the generated text is semantically correct but does not fit the gold standard of the corpus, it is modified to fit the standard.

Confusion matrix for the Named Entity Recognition task on the HDI dataset. The BILUO tagging scheme is used. Red indicates a higher match between the classes, while blue indicates lower matches. White indicates that no match occurred. Values are normalized along columns for better visualization of errors.

In our experiments (based on sentence-chunked inputs), this difference is less visible, but may be more pronounced with longer texts.

While generative models provide flexibility, our results suggest that small-scale generative models underperform compared to traditional models in this task. Larger generative models may narrow this gap, but at a cost in computational resources.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we introduce and describe a newly developed dataset specifically designed for the task of Named Entity Recognition (NER) in the context of Herb-Drug Interactions (HDIs). This dataset has been carefully constructed using both clinical and pre-clinical scientific studies that are publicly available through the PubMed database. It is unique in that it not only focuses on identifying entities directly involved in interactions, such as drugs and herbs, but also incorporates entities that provide contextual information surrounding these interactions—such as dosage, patient characteristics, or environmental factors. This dual focus enhances the richness of the dataset and broadens its potential utility in various biomedical applications. To the best of our knowledge, there currently exists no other publicly available dataset that is tailored specifically for the study of HDIs, particularly one that includes context-related entities in addition to the primary interacting components. This makes our dataset a novel and valuable resource for the research community working on biomedical text mining and pharmacovigilance.

We validate the usefulness and quality of our dataset annotations by applying them to standard NER tasks and benchmarking the performance against a widely recognized dataset with similar objectives: the Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) corpus. Our experiments demonstrate that the inter-annotator agreement among a selected group of expert annotators is consistently high, which supports the reliability and consistency of the annotation process.

Moreover, our results show that models trained on our HDI-specific dataset achieve performance metrics that are only slightly lower than those achieved using the DDI corpus, when comparing the same models across equivalent types of entities. This finding suggests that our corpus has strong potential for training machine learning models, even though it is newly introduced. However, we observed that certain types of entities, especially those that are either underrepresented in the dataset or inherently more complex and ambiguous, tend to yield lower prediction accuracy. Examples of such entities include specific patient demographics, less common herbal substances, and context descriptors. In contrast, more frequently encountered entities—such as the names of widely used drugs, common herbs, and prevalent pathologies—are identified with significantly higher accuracy. The difficulty in predicting context-related entities may be attributed to the variability and lack of standardized structure in how this information is presented in text.

In addition to conventional NER methodologies, we also explored the application of generative language models for extracting relevant information from biomedical text. Our findings indicate that generative AI offers notable advantages in terms of adaptability and ease of use, as it eliminates the necessity of retraining a new model for each specific task. However, this flexibility comes with trade-offs, particularly in the areas of performance consistency, versatility across different entity types, and increased computational resource demands.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AI | = Artificial Intelligence |

| NLP | = Natural Language Processing |

| NHP | = Natural Health Product |

| NER | = Named Entity Recognition |

| DDI | = Drug-Drug Interaction |

| HDI | = Herb-Drug Interaction |

| LLM | = Large Language Model |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions. FS thanks LMS for her curiosity. AC thanks GC and SC for their support and valuable discussions.