Improving Feature Selection for Infant Mortality Risk Assessment via Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization

Abstract

Introduction

Infant mortality is a pivotal indicator of community health and socioeconomic conditions. Despite global advancements in healthcare and significant reductions in infant mortality rates, substantial disparities persist, particularly in underserved populations. This research aims to tackle these disparities by enhancing the predictive accuracy of public health interventions. We utilize advanced feature selection techniques to identify critical predictors of infant survival, thereby supporting the development of targeted and effective health policies and practices.

Methods

We introduce an enhanced Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization algorithm (BMOCO), specifically designed for feature selection in extensive medical datasets. The suggested method focuses on optimizing eight S-shaped and V-shaped transfer functions to refine the conversion of continuous position vectors into binary form, ensuring precise feature selection and robust model performance.

Results

The BMOCO method demonstrates superior accuracy and effectiveness in feature selection compared to traditional evolutionary optimization algorithms such as MOGA (Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm), MOALO (Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimizer), NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II), and MOQBHHO (Multi-Objective Quadratic Binary Harris Hawk Optimization). Applied to U.S. infant birth data, our approach achieves an average classification accuracy of 99.54%. Critical factors impacting infant mortality identified include maternal literacy, prenatal care frequency, and pre-existing maternal conditions, such as diabetes, smoking during pregnancy, body mass index, infant birth weight, and breastfeeding practices. These findings indicate that the optimized BMOCO model provides interpretable and data-driven insights that align with established clinical evidence.

Discussion

The results underscore the effectiveness of advanced machine learning techniques in uncovering significant health predictors.

Conclusion

The proposed BMOCO algorithm offers a robust and interpretable tool for health professionals to enhance predictive models, facilitating targeted interventions to reduce infant mortality rates and improve public health outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The global health landscape has faced unprecedented challenges due to ongoing pandemics, underscoring the vulnerability of specific populations, including pregnant women. These conditions have significantly heightened concerns about neonatal outcomes, emphasizing the crucial role of maternal health in both infant well-being and the broader public health ecosystem. Defined as children from birth to the end of their first year, infants are highly vulnerable during this critical initial phase of life. The Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), quantified as the number of deaths per 1,000 live births, is a vital indicator of public health and societal well-being [1]. This metric is subdivided into perinatal, neonatal, and post-neonatal categories, each presenting unique challenges and risk factors. Common causes of post-neonatal mortality include malnutrition, respiratory diseases, complications arising from pregnancy, sudden infant death syndrome, and socio-economic issues [2].

As of the first quarter of 2024, the IMR in the U.S. was approximately 5.55 per 1,000 live births [3], while worldwide, the IMR was 25.519 per 1000 live births [4]. Notably, the IMR in India was 25.799 deaths per 1000 live births in 2024 [5], starkly contrasting with the U.S.’s IMR and those of European countries and other developed OECD countries. In developing countries like India, the high IMR values underscore the need for targeted public health interventions. These disparities highlight significant differences across the world in healthcare systems, poverty levels, and public health policies. Moreover, inequalities in IMR across various racial groups are reported for the U.S. and other countries. These findings are profound and troubling, underlining that health equity remains an elusive goal despite ongoing efforts worldwide [6]. While significant progress has been made in healthcare, the persistence of high IMR in specific demographics starkly illustrates the complex interplay of maternal health, healthcare accessibility, and socio-economic conditions [7, 8]. These factors are critical not only in understanding but also in improving a nation’s health outcomes. The increase in premature and low-birth-weight births has further complicated the landscape, necessitating focused research to mitigate these risks and effectively reduce infant mortality rates [9, 10].

In this context, the current research paper introduces an advanced Feature Selection (FS) technique using the Cheetah optimization algorithm [11] to identify the most significant predictors of infant survival. The presented approach aims to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of health interventions, ultimately improving neonatal outcomes. In our research, we utilize extensive U.S. birth record data from 2016 to 2022, sourced from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) [12].

Efficient FS is paramount in modern data analytics, particularly in healthcare, where the stakes are high, and serious problems can arise when analyzing data incorrectly [13, 14]. Redundant or irrelevant features can obscure significant patterns and insights in health data, leading to inefficient models and potentially harmful misdiagnoses. Metaheuristic algorithms, extensively reviewed in a previous study [15-19], provide a robust framework for addressing these challenges. These algorithms have shown considerable promise across various application areas, from economic forecasting to healthcare, by significantly enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of conventional predictive models [20, 21]. In response to these challenges, this research introduces a crowding distance-based Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) method. This sophisticated approach aims to improve the selection of pertinent features from large datasets, potentially enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of predictive models used for infant health assessments. By optimizing the FS process, we aim to reduce redundancy and focus on the most impactful variables influencing infant health and mortality outcomes, thereby facilitating more accurate and reliable infant health prediction.

The proposed approach employs cutting-edge machine learning techniques, reflecting our aim to bridge the gap between theoretical/computational advances and practical healthcare applications. By harnessing the power of detailed data analysis and FS, we provide actionable insights that can lead to effective policy interventions and improved clinical practices, particularly for infant care and infant health. Thus, from a broad perspective, the current research underscores the importance of integrating data science with public health strategies to tackle the leading causes of infant mortality, aiming to foster a healthier future for the next generation.

Several key innovations in feature selection and predictive modeling for infant healthcare data analysis are introduced in this paper [22]:

1.1. Enhanced Binary Multi-objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO)

We propose an improved version of the Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization method, tailored for feature selection in large-scale, high-dimensional medical datasets. The enhancement incorporates dynamic control mechanisms that regulate the balance between exploration and exploitation to achieve better convergence.

1.2. Optimized Transfer Functions for Binary Conversion

To improve the transformation of continuous position vectors into binary format, eight S-shaped and V-shaped transfer functions are systematically evaluated and optimized. This optimization enhances the precision and robustness of the feature selection process, which is especially important when working with sensitive medical data.

1.3. Comprehensive Benchmarking Against State-of-the-art Algorithms

The proposed BMOCO method is extensively benchmarked against several leading multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, including MOGA [16], MOALO [23], NSGA-II [24], and MOQBHHO [17], demonstrating its competitive advantage.

1.4. Application to Real-world Infant Mortality Datasets

The proposed methodology is validated on real-world U.S. birth datasets. In addition to enhancing classification accuracy, the method identifies key predictors of infant mortality, such as birth weight, maternal education, and prenatal care frequency, providing actionable insights for healthcare practitioners.

1.5. Framework for Data-driven Public Health Decision-making

This work establishes a methodological foundation for leveraging advanced optimization and machine learning techniques to inform targeted public health interventions, particularly those aimed at reducing infant mortality rates in underserved populations.

1.6. Background and Related Work

Research into neonatal health through predictive analytics has become increasingly vital as data science and machine learning technologies advance. It provides a comprehensive review of significant contributions in the relevant literature, focusing on methodologies and findings that directly influence the understanding and prediction of infant health and mortality. In recent studies, various maternal characteristics were scrutinized using logistic regression, naive Bayes, and linear support vector machines on data from U.S. Territories in 2013 [25]. These analyses have provided insights into dangerous maternal factors significantly impacting neonatal survival rates. Similarly, Gaussian Process Classification was proposed to predict hospital mortality among neonates, showcasing the potential of advanced probabilistic models in healthcare settings [26]. The application of machine learning techniques to assess the cost-effectiveness of long-term newborn care was explored, demonstrating the utility of predictive models in managing healthcare costs effectively [27].

Research has consistently highlighted the strong correlation between neonatal deaths and premature births. Predictive models were created using data from Italian neonates and subsequently tested and validated across various temporal settings, demonstrating their robustness and adaptability [28]. Furthermore, machine learning techniques were employed in Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) to assess short-term mortality, which has crucial implications for clinical decision-making and treatment optimization [29]. Exploring maternal traits associated with Small Gestational Age (SGA) has been crucial for early identification of at-risk neonates, particularly in resource-limited settings [30]. Different socioeconomic characteristics, such as maternal education and birth order, were analyzed to predict infant mortality using a three-year comprehensive dataset, which provided deep insights into the social determinants of health [31].

Despite all these significant advancements, the evolution of methodologies for effectively selecting variables that predict infant mortality still needs to be improved. A study utilized a dataset of 275 neonates to demonstrate how random forest models could excel in predicting preterm neonatal death, emphasizing the need for high sensitivity and specificity in predictive models [32]. Adapting swarm-based optimization methods, inspired by the foraging and hunting behaviors of untamed creatures, introduces another novel approach to feature selection in predictive modeling [33-35]. Specifically, the cheetah’s unique hunting strategies have inspired algorithms that balance efficiency with the ability to cover extensive search areas [11]. Evolutionary strategies such as these can improve algorithmic performance by adapting search tactics based on the success of previous attempts, thereby showcasing flexible problem-solving in dynamic environments [36].

The feature selection task can be framed as a binary optimization problem [37] where the transfer function plays a pivotal role [38]. This function is essential for converting a numeric search space into a discrete domain, a step that is crucial for applying a binary optimization method effectively [39]. Optimizing transfer functions and feature subsets has been emphasized as a means to enhance the exploration and exploitation capabilities of algorithms, thereby avoiding local optima and improving overall model performance. Integrating machine learning with traditional epidemiological approaches has also opened new avenues for understanding complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and social factors contributing to neonatal outcomes [28]. Such a multidisciplinary approach could enable a more comprehensive understanding of the causes of infant health and mortality, which is crucial for developing more targeted interventions.

In summary, the reviewed literature highlights the critical role of feature selection and predictive modeling in advancing neonatal health analytics. Despite notable progress, there remains a pressing need for more adaptive, scalable, and interpretable methods that can effectively extract meaningful predictors from high-dimensional datasets. This study addresses this gap by proposing an optimized feature selection framework grounded in evolutionary computation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Foundations of Cheetah-Based Multi-objective Feature Selection

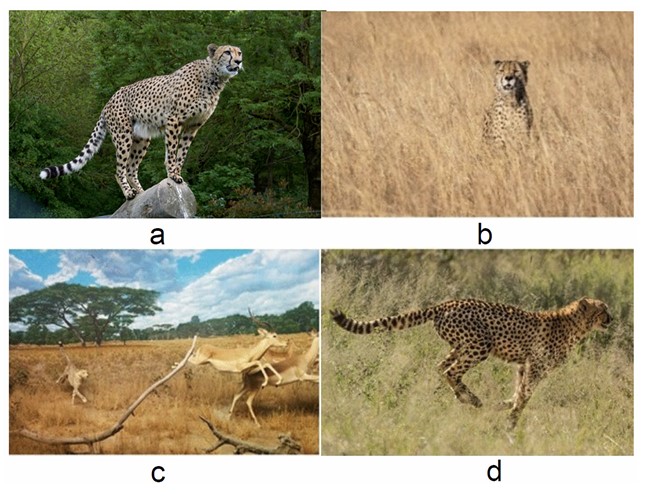

We delve into the advanced optimization techniques underpinning the current research study, focusing on integrating Cheetah Optimization and Multi-Objective Optimization to address the complex challenges inherent in predicting infant mortality. These approaches capitalize on the inherent patterns and behaviours observed in nature and adapt them to address the challenges of intricate, high-dimensional spaces, which are often typical of medical data analytics. The proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) method represents an approach specifically tailored to manage the discrete complexities of high-dimensional datasets effectively, particularly for feature selection. By balancing the accuracy of feature selection with the overarching goal of model simplicity, BMOCO aims to enhance predictive performance while minimizing computational demands. It outlines a detailed description of the Cheetah Optimization Algorithm and the theoretical foundations of multi-objective optimization. The Cheetah Optimization Algorithm (COA) [11] is a novel, population-based optimization approach inspired by cheetahs’ dynamic and strategic hunting behaviour. Before discussing the specifics of the COA, it is important to visualize how a cheetah approaches its hunt. Figure 1 illustrates the hunting strategies employed by cheetahs, highlighting their strategic and responsive nature, which the algorithm seeks to emulate computationally. The cheetah's hunting strategy often begins with a period of vigilance. When a cheetah sights a target (prey) in its surroundings, it may choose to remain stationary and wait for the prey to move closer before launching an attack. This attack mode typically involves stages of stirring and entrapping. Conversely, the cheetah may abandon the hunt for several reasons, such as fatigue or the prey's rapid movement. In such cases, the cheetah may take a break and subsequently return to hunting after a pause. The cheetah selects the optimal tactic by assessing the target’s (prey) state, location, and proximity (Fig. 1a-d) [11]. The COA mimics these natural tactics to address optimization problems, integrating biologically inspired strategies to enhance algorithmic efficiency and adaptability.

Specifically, the COA model adapts to dynamic target (prey) availability and the cheetah’s physical state, employing a blend of passive and active hunting tactics. These strategies are designed to optimize energy expenditure and increase the probability of successful hunts, directly analogous to optimizing computational resources and solution accuracy in complex optimization scenarios.

Illustration of various hunting strategies employed by cheetahs: (a) Observing the prey, (b) Perching and awaiting, (c) Running, (d) Trapping.

2.1.1. Search Strategy

The COA models the cheetah’s prey-search behaviour by employing either an active patrol or a passive wait approach, depending on the density and behaviour of the target (prey).

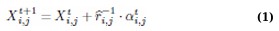

In scenarios where the target (prey) is abundant and stationary, the algorithm adopts a scanning mode from a fixed position, thereby maximizing energy efficiency. Conversely, when the target (prey) is dispersed, it necessitates an active, energy-intensive search strategy. This adaptability is mathematically modelled as follows: (Eq. 1)

where Xi,jt+1 is the cheetah's next position, Xi,jt is the current position, t is the current time,  and αi,jt represent the randomization parameter and step length, respectively. This dual-mode hunting strategy reflects the algorithm’s ability to switch between exploration and exploitation, optimizing the search for optimal solutions.

and αi,jt represent the randomization parameter and step length, respectively. This dual-mode hunting strategy reflects the algorithm’s ability to switch between exploration and exploitation, optimizing the search for optimal solutions.

2.1.2. Sit-and-wait Strategy

This energy-conserving strategy involves the cheetah lying in wait, minimizing its movements to avoid alerting nearby targets (prey). The algorithm mirrors this behaviour by maintaining the position until optimal conditions for an attack arise, thus saving computational resources and focusing efforts only when high-quality solutions are within reach: (Eq. 2)

2.1.3. Attack Strategy

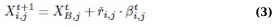

Mirroring the cheetah’s rapid chase, this strategy is activated when the target (prey) is within optimal range. The algorithm calculates the trajectory for an effective intercept, utilizing speed and tactical repositioning, which represents a rapid convergence towards the best-known solution: (Eq. 3)

where XB,jt indicates the best current position of the target (prey), and rˇi,j, and βi,jt are the turning and interaction factors, respectively.

2.1.4. Fundamentals of Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO)

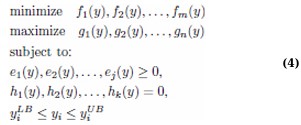

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) involves optimizing multiple conflicting objectives simultaneously, a common challenge in complex decision-making scenarios [40]. The goal is to find a solution that achieves the best possible balance among competing objectives. Mathematically, an MOO problem can be formulated as follows: (Eq. 4)

In the above formulation, f1, f2,..., fm and g1, g2,..., gn are the objective functions to be minimized and maximized, respectively. ej and hk represent the inequality and equality constraints the solutions must satisfy, with yiLB and yiUB denoting the lower and upper bounds of the decision variables yi. The concept of dominance is crucial to this approach. A solution p1 is said to dominate another solution p2 if it performs better in at least one objective without being worse in any of the others. Optimal solutions form a Pareto front, a benchmark for evaluating trade-offs among competing objectives [41]. This approach enables a holistic view of potential solutions, often leading to innovative outcomes that traditional single-objective optimization might overlook [42-44].

Despite its potential, the literature suggests the need for further research on multi-objective evolutionary approaches to feature selection in health data. Exploring this gap can lead to significant advancements in the analysis and understanding of complex medical datasets, offering a balanced approach to predictive accuracy and computational efficiency and ultimately enhancing patient outcomes. The exploration of advanced optimization techniques sets a solid foundation for the methodologies employed in this study, aiming to leverage these sophisticated algorithms to improve predictive models of infant health outcomes. The integration of these techniques represents a convergence of biological inspiration and mathematical precision, poised to make significant contributions to healthcare analytics. Such an evolutionary-based advanced optimization approach is Cheetah Optimization for feature selection.

2.2. Proposed Method

The study presents the proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) model in detail, outlining its algorithmic components and the workflow for feature selection in high-dimensional medical datasets. Inspired by the adaptive hunting behavior of cheetahs, BMOCO incorporates multiobjective optimization principles and a dynamic transfer function mechanism to identify the most relevant features while maintaining classification accuracy. The method is structured around several key components, including position encoding, fitness evaluation, archive management, and strategy-driven position updates. Each component contributes to a flexible and efficient search process capable of handling the complexities of large-scale health data.

2.2.1. Motivation Behind Cheetah Optimization for Feature Selection

The integration of Cheetah Optimization (CO) into the Feature Selection (FS) domain is motivated by several distinct qualities of the CO algorithm that make it particularly appealing for addressing complex optimization challenges:

2.2.2. Novelty and Adaptability

The CO [11] is a relatively new optimization algorithm, and its potential across various application domains remains largely untapped. The exploratory nature of this algorithm makes it ideal for testing in uncharted territories of optimization problems, including feature selection in healthcare data analytics.

2.2.3. No Free Lunch Theorem

According to the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem [45], no single algorithm can optimally solve all optimization problems. This theorem supports the rationale for exploring novel approaches like CO in diverse settings, including feature selection, where traditional methods may fail.

2.2.4. Simplicity and Efficiency

Unlike other optimization methods that rely heavily on complex mathematical formulations, CO utilizes straightforward procedures enhanced by strategic hunting behaviours. This simplicity allows for efficient search space exploration while maintaining the algorithm’s robustness.

2.2.5. Balance between Exploration and Exploitation

CO’s hunting strategies prevent premature convergence, a common issue in optimization tasks. By enabling a balanced approach to exploration (searching through diverse areas of the search space) and exploitation (intensifying the search around promising areas), CO ensures a thorough investigation of potential solutions.

Conceptual framework of the proposed feature selection methodology using BMOCO.

2.2.6. Innovation in Multi-objective Optimization

Although initial attempts have been made to apply cheetah-inspired strategies in feature selection, the domain still lacks comprehensive studies, especially concerning multi-objective optimization with parallel transfer function optimization. This gap presents a significant opportunity to innovate and improve feature selection methodologies, especially in high-dimensional data scenarios.

These unique aspects of CO prompted us to investigate its application to the feature selection domain, aiming to leverage its capabilities for enhancing effectiveness and efficiency in selecting relevant features. This approach is expected to contribute to the literature by providing a new perspective on optimizing feature selection processes in complex datasets.

2.2.7. Feature Selection Using Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO)

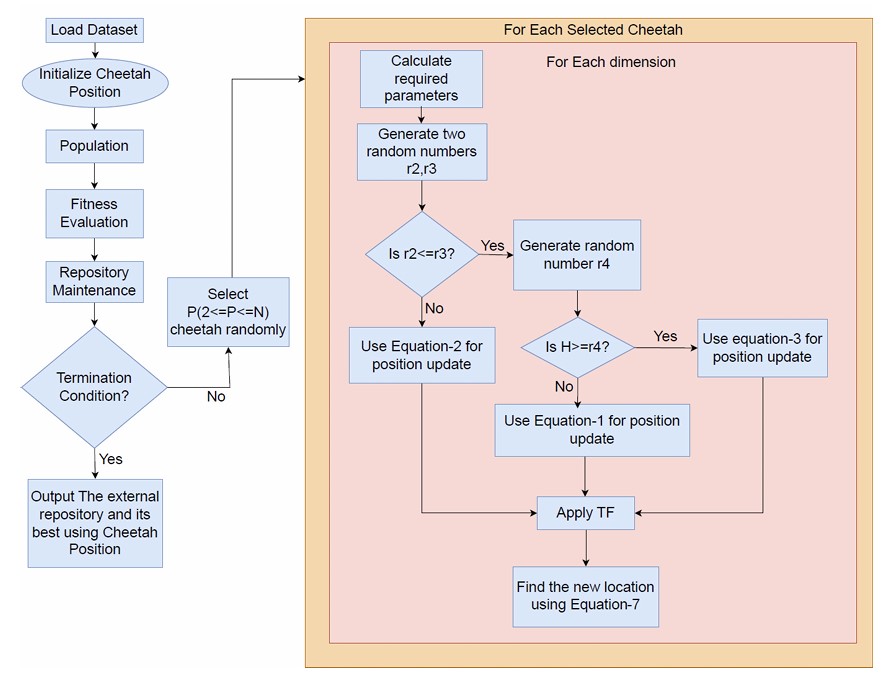

Figure 2 displays the conceptual framework of the proposed feature selection methodology using the binary version of Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO). This adaptation addresses the discrete nature of the feature selection problem, where features are either selected or not, making the original continuous-domain CO algorithm unsuitable without modifications [11].

The adjustments necessary to adapt CO for feature selection are outlined as follows:

2.2.7.1. Position Encoding

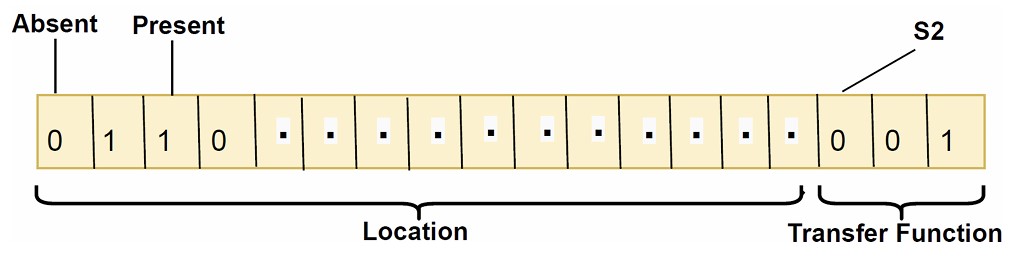

In BMOCO, each cheetah is represented by a binary string of length L + 3 (where L is the number of features in the dataset). This encoding is crucial for the discrete nature of feature selection, where each bit in the string (0 or 1) signifies the exclusion or inclusion of a feature, and the additional three bits determine the choice of transfer function used during optimization. Figure 3 illustrates this binary position encoding.

2.2.7.2. Fitness Computation

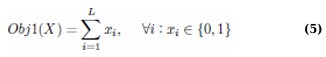

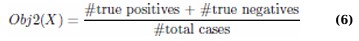

The fitness of each cheetah’s configuration in BMOCO is evaluated based on two primary objectives: (Eq. 5)

The first objective, Obj1, aims to minimize the number of features selected to simplify the model and reduce overfitting. This reduction is crucial in enhancing model generalizability and computational efficiency. (Eq. 6)

Where X represents the position vector of a cheetah. To compute Obj2 features corresponding to ones in X, compress the dataset, and evaluate classification performance using a KNN classifier and 10-fold cross-validation.

2.2.7.3. External Archive Maintenance

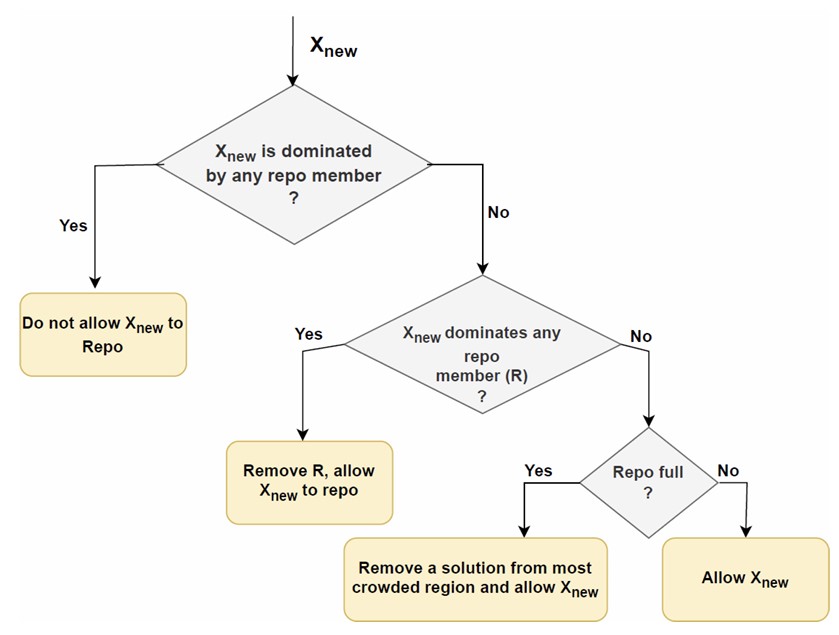

An external archive is crucial for storing non-dominated solutions identified during optimization. It maintains diverse solutions, reflecting the best trade-offs between minimizing feature count and maximizing classification accuracy. This approach is vital for handling multi-objective optimization’s inherent complexities and ensuring a broad solution for space exploration. To introduce the external archive’s management, Figure 4 depicts how solutions are evaluated and either retained or replaced based on their dominance relations.

2.2.7.4. Transfer Function Optimization

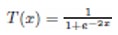

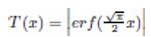

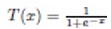

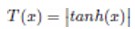

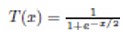

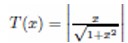

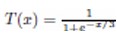

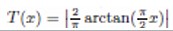

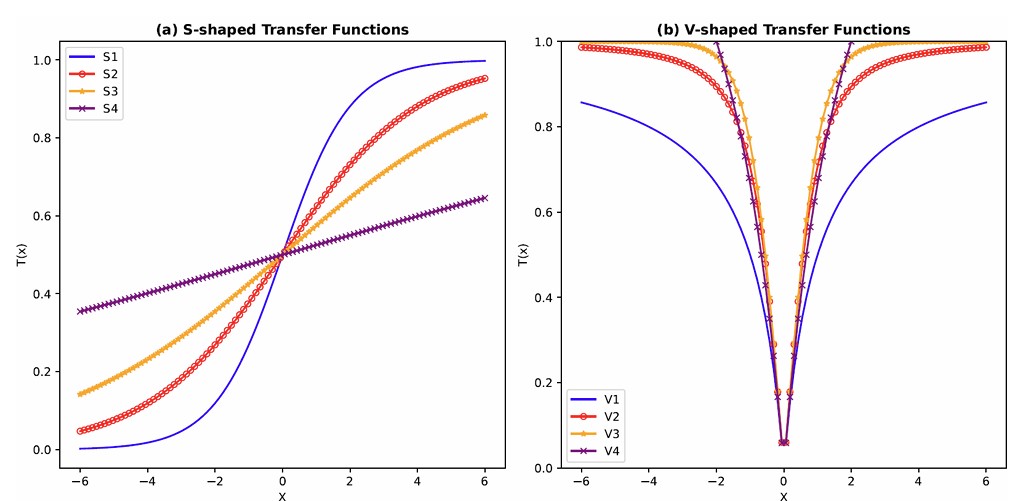

The adaptation of transfer functions in BMOCO is essential for effectively navigating the binary search space. These functions adjust the probabilities of bit flips in a cheetah’s position vector, influencing the exploration and exploitation dynamics within the algorithm. This nuanced handling helps significantly enhance the convergence behaviour, allowing the algorithm to effectively escape local optima and ensuring a comprehensive search across the feature space. Before diving into the specific functions used, it is beneficial to understand the variety and purpose of each transfer function employed. These functions are designed to modify the solution space navigation differently, optimizing the search and solution refinement processes as depicted in Table 1.

Figure 5a, b illustrates the visual appearance of the eight transfer functions. In each iteration, after assessing the fitness of the members of the cheetah population, the set of non-dominated solutions is identified and strategically arranged in reverse order based on Crowding Distance (CD) values. The solution with the highest CD value is then selected as the ’prey,’ and the corresponding transfer function is adopted for the subsequent step of the process. It is important to note that although the transfer function is selected dynamically during the run, it is not updated once chosen.

| S-Shaped TFs | V-Shaped TFs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Function | Bits | Name | Function | Bits |

| S1 |  |

000 | V1 |  |

100 |

| S2 |  |

001 | V2 |  |

101 |

| S3 |  |

010 | V3 |  |

110 |

| S4 |  |

011 | V4 |  |

111 |

Binary position encoding of each cheetah in BMOCO, highlighting feature inclusion and transfer function selection.

Detailed management process of the external archive in BMOCO.

Visual representation of (a) S-shaped and (b) V-shaped transfer functions used in BMOCO.

The selection of transfer functions within BMOCO is pivotal in effectively navigating the solution landscape. Each transfer function modifies the probability distribution for selecting features, thus influencing the algorithm’s balance between exploration and exploitation. By adopting these functions dynamically based on the optimization state, BMOCO can maintain diversity in the solution pool while efficiently converging to optimal solutions.

Three additional bits in each cheetah’s position string are used to select among these eight transfer functions, further tailoring the search process to the specific dynamics of the feature selection landscape. In each iteration, after assessing the fitness of each cheetah, the set of non-dominated solutions is strategically arranged in reverse order of crowding distance (CD) values. The highest CD value solution is then selected as the ’prey,’ guiding the subsequent search direction. The selected transfer function significantly impacts how the search progresses, ensuring adaptability and robustness in the search strategy.

2.2.7.5. Position Update

The position update mechanism in BMOCO reflects the adaptive strategies cheetahs employ in the wild, balancing energy conservation during the search phase and aggressive pursuit during attacks.

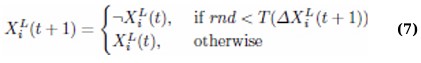

When hunting, either the seeking or the attacking strategy may be applied depending on the context, but as the cheetah’s energy declines, the likelihood of switching to the search strategy increases. During the early iterations, the algorithm emphasizes exploration through the search method, while later iterations favor exploitation by applying the attack strategy to refine candidate solutions. The transition between strategies is controlled using random thresholds. If r2 ≥ r3, the cheetah adopts a sit-and-wait approach, and its position remains unchanged as per Eq. (2). Otherwise, the value of r1—a random number in [0, 1]—is used to compute H = e2(1−t/T)(2r1 − 1), which governs the strategy choice. If H ≥ r4, the attack strategy is employed using Eq. (3); otherwise, the search strategy in Eq. (1) is used. The prey’s location is defined as the solution with the highest crowding distance in the current archive, representing a high-quality, sparsely crowded solution. The selected transfer function from the prey is then used to probabilistically update the cheetah’s position via Eq. (7), allowing efficient exploitation of promising regions of the search space [38].

Where rnd is a random number between [0,1], X represents the cheetah’s position, L is the dimension, t is the current iteration, ¬ denotes negation, and T () is the chosen transfer function. Random thresholds govern the sit-and-wait approach and an active search-and-attack. This ensures that the strategy shifts dynamically based on the situation, reflecting the real-time decision-making processes observed in natural cheetah behaviour.

2.2.7.6. BMOCO Algorithm

The BMOCO Algorithm 1 encapsulates the entire feature selection process, from initialization to the final selection of optimal feature sets based on crowding distance. This process ensures the algorithm finds non-dominated solutions regarding feature count and classification accuracy, representing a balance between these competing objectives. BMOCO’s computational complexity primarily depends on the number of features and the size of the dataset. Each algorithm iteration evaluates all individuals in the population across the entire feature set, making the computational cost proportional to the product of these factors. This scaling is crucial in high-dimensional data, where efficient handling of large feature sets becomes imperative.

2.2.7.7. Selection of the Crowding Distance-Based Optimal Solution from the Repository

After a specified number of iterations, the external archive, filled with non-dominated solutions, is assessed to identify the optimal set of features. This selection uses the Crowding Distance (CD) metric, which measures density around each solution in the objective space, ensuring that the selected features are practical and diverse [17].

This comprehensive approach, embodied in the BMOCO algorithm, harnesses the dynamics of natural predation and adapts them for complex, high-dimensional feature spaces, driving towards solutions that offer a practical balance between minimal feature sets and maximum classification accuracy.

Algorithm 1 BMOCO-Based Feature Selection

Input: Population size N, Maximum iterations MaxIt, Dataset D

Output: Optimized feature set A in external archive 1: Initialize the population of cheetahs randomly.

2: Calculate initial objective values Obj1 and Obj2 for each cheetah.

3: Store the non-dominated solutions in an external archive. 4: fori = 1 to MaxIt do

5: Select K (where 2 ≤ K ≤ N) cheetahs randomly. 6: for all cheetahs in the selection do

7: Calculate rˆ, rˇ, α, β, and H based on current and local best positions. 8: Generate random numbers r2, r3, r4 uniformly distributed in [0, 1].

9: if r2 ≤ r3 then

10: if H ≥ r4 then

11: Update the position of the cheetah using the attack strategy equation. 12: else

13: Update position using the search strategy equation. 14: end if

15: else

16: Maintain position using a sit-and-wait strategy. 17: end if

18: Apply the appropriate transfer function.

19: Recalculate objective values Obj1 and Obj2.

20: Update the external archive with new non-dominated solutions. 21: end for

22: end for

23: Return the best solution from the archive based on Crowding Distance (CD).

2.3. Experimental Setup and Benchmarking

It outlines a comprehensive experimental framework designed to assess the effectiveness of the BMOCO method in feature selection tasks. It details the computational setup, the datasets employed, and the benchmarking algorithms against which BMOCO is compared. This framework facilitates a robust, reproducible, and fair evaluation by aligning computational settings, classifier choice, and metric definitions across all comparative algorithms. This rigorous evaluation not only underscores the adaptability and efficiency of BMOCO but also situates it within the broader context of existing multi-objective optimization methods. We further elucidate the dataset’s structure, the preprocessing steps to ensure data quality, and a suite of multi-objective performance indicators used to measure the efficacy of the proposed and existing methods. This methodical approach ensures a thorough understanding and validation of the optimization capabilities of BMOCO, aiming to establish new benchmarks in feature selection for complex datasets.

2.3.1. Benchmark Algorithms for Performance Comparison

We compare the efficacy of the Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) approach to rigorously evaluate it against four established benchmarking algorithms tailored explicitly for feature selection tasks. These algorithms include MOGA-FS (Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Feature Selection) [16], MOALO-FS (Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimizer for Feature Selection) [23], NSGA-II-FS (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II for Feature Selection) [24], and MOQBHHO-FS (Multi-Objective Quadratic Binary Harris Hawk Optimization for Feature Selection) [17]. Each method has been selected based on relevance and proven performance in similar optimization scenarios, providing a robust basis for comparison.

The experimental framework uses Python 3.7 on a computer with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i3-6006U CPU at 2.00GHz and 8.00 GB of RAM. This setup ensures the computational environment is controlled and consistent, allowing reproducible results.

We utilize the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier with K set to 5 and a 10-fold cross-validation procedure for the classification accuracy measurement. This classifier is chosen for its simplicity and effectiveness in handling various data types without requiring explicit adjustments to the training phase. KNN operates on a simple principle: it classifies new cases based on a majority vote of their k nearest neighbours, where the case is assigned to the class most common among them, measured by a distance function. KNN is instance-based: it stores the training set and classifies new samples by a majority vote among the k nearest neighbors.

Specific parameter settings for each optimization algorithm are meticulously defined to ensure comprehensive assessment, as shown in Table 2.

These parameter configurations are harmonized with those commonly used in evolutionary and swarm intelligence algorithms, ensuring experimental consistency and enabling a focused evaluation of the performance benefits introduced by BMOCO.

2.3.2. Dataset Characteristics and Preprocessing for BMOCO Evaluation

To evaluate the BMOCO method, we utilize birth data collected across seven standard U.S. Territories from 2016 to 2022. These datasets are sourced from the National Center for Health Statistics [12] and are instrumental in assessing the effectiveness of the feature selection process facilitated by BMOCO. Each dataset shares a consistent structure, enabling reliable comparative analysis over time. Table 3 provides an overview of sample sizes, features, and class distribution across years.

We used the complete birth records for each year rather than subsampling to retain full clinical and demographic variability, including rare but important patterns. While formal power analysis is typical in hypothesis-driven clinical studies, large-scale real-world data combined with 10-fold cross-validation offers strong empirical reliability in machine learning settings and ensures robust model performance evaluation.

Each sample was normalized to ensure computational stability and fairness in distance-based classification. Normalization ensures that all features contribute equally in KNN classification, preventing scale-based distortion.

This data structure provides a robust basis for applying and validating BMOCO, facilitating an in-depth analysis of the algorithm’s performance in selecting relevant features that can accurately predict outcomes across varied sample sizes and consistent feature dimensions.

| Parameters | BMOCO | MOGA-FS | MOALO-FS | NSGA-II-FS | MOQBHHO-FS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Iterations | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| #Individuals | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Repository Size | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Crossover Rate | - | - | - | 0.8 | - |

| Mutation Rate | - | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | - |

| S.NO. | Dataset Year | No. of Samples | No. of Features | No. of Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2016 | 35,185 | 1330 | 3 |

| 2 | 2017 | 29,851 | 1330 | 3 |

| 3 | 2018 | 25,919 | 1330 | 3 |

| 4 | 2019 | 24,373 | 1330 | 3 |

| 5 | 2020 | 23,484 | 1330 | 3 |

| 6 | 2021 | 23,448 | 1330 | 3 |

| 7 | 2022 | 23,011 | 1330 | 3 |

2.3.3. Evaluation Metrics for Multi-objective Optimization in Feature Selection

Various well-regarded multi-objective evaluation metrics have been utilized to assess the performance of the BMOCO method against established benchmarks in feature selection. These metrics provide a comprehensive view of how well each method performs across multiple objectives and can be used to identify the most effective approach for handling complex datasets from newborn screening [46]. The metrics that we have used are as follows:

2.3.4. Generational Distance (GD)

This metric measures the Euclidean distance between the solutions obtained by the algorithm (computed front, A) and the true Pareto front (PF). It is defined as: (Eq. 8)

A smaller value of GD indicates that the computed solutions are closer to the Pareto front, reflecting higher solution quality. In this study, the actual Pareto front is estimated by pooling and filtering non-dominated solutions from multiple runs of all algorithms, as suggested by [47].

2.3.5. Inverted Generational Distance (IGD)

Complementary to GD, IGD measures how well a set of solutions approximates the true Pareto front: (Eq. 9)

An optimal algorithm would minimize IGD, indicating comprehensive coverage and proximity of its solutions to all members of the actual Pareto front.

2.3.6. HyperVolume (HV)

HV quantifies the volume covered by the members of the computed Pareto front (A) in the objective space. It is bounded by a reference point rp ∈ Rm, ensuring all solutions in A dominate rp. A higher HV value suggests a better spread and convergence of solutions within the objective space.

2.3.7. Spread

This metric evaluates the diversity of solutions across the Pareto front by measuring the extent of spread among all objective function values: (Eq. 10)

A desirable property for an effective optimization is a broader spread, which indicates a diverse set of solutions spanning possible trade-offs between objectives.

Employing these metrics provides a robust framework for comparing the effectiveness and efficiency of various multi-objective feature selection methods, aiding in identifying the most suitable algorithm for handling the complexity and nuances of newborn dataset feature selection.

3. RESULTS

It presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) method alongside a comparison with other benchmark multi-objective feature selection methods. Employing U.S. infant mortality datasets, we assess the efficacy of BMOCO and its competitors across various metrics designed to capture both the efficiency and effectiveness of each method in feature selection. These metrics include Pareto front approximations, objective function metrics, statistical tests, execution time, and multi-objective performance measures. The comprehensive analysis not only highlights the strengths and weaknesses of BMOCO but also situates it within the current landscape of advanced feature selection techniques used in healthcare analytics.

3.1. Performance Comparison based on Pareto Fronts

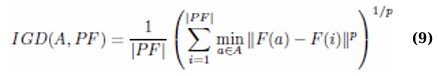

It delves into the comparative performance of the suggested Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) method against established benchmarks using the representation of Pareto fronts. Pareto fronts illustrate the trade-offs between conflicting objectives, such as minimizing feature count while maximizing classification accuracy. By examining these fronts, we can evaluate each method’s effectiveness in balancing model simplicity with predictive performance.

The Pareto fronts depicted in Figure 6 show that those from BMOCO are consistently closer to the true Pareto fronts across all datasets. This proximity indicates that BMOCO efficiently generates solutions that reduce the number of features used and maintain or enhance classification accuracy. A detailed analysis reveals that BMOCO outperforms other methods, particularly in its ability to identify critical predictive features with fewer indicators, as evidenced by the high accuracy rates achieved with significantly reduced feature sets.

Comparison of pareto fronts obtained from BMOCO and benchmark methods after 30 iterations.

| Datasets | Before FS | After FS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOGA-FS | MOALO-FS | NSGA-II-FS | MOQBHHO-FS | BMOCO-FS | ||

| 2016 | [1330, 96.6] | [51, 98] | [21, 95.5] | [47, 97.3] | [30, 96] | [18, 96.1] |

| 2017 | [1330, 97.44] | [52, 99] | [25, 98.5] | [47, 99.3] | [18, 99.2] | [41, 99.7] |

| 2018 | [1330, 97.79] | [55, 99.5] | [53, 99.6] | [47, 99.5] | [56, 99.8] | [38, 99.7] |

| 2019 | [1330, 97.25] | [52, 99.4] | [50, 99.7] | [46, 99.5] | [60, 99.8] | [37, 99.7] |

| 2020 | [1330, 96.45] | [52, 99.4] | [50, 99.7] | [41, 99.2] | [50, 99.8] | [37, 99.7] |

| 2021 | [1330, 97.99] | [50, 99.6] | [50, 99.7] | [43, 99.2] | [36, 99.4] | [41, 99.7] |

| 2022 | [1330, 97.7] | [44, 99.6] | [44, 99.7] | [43, 99.2] | [42, 99.6] | [18, 99.2] |

Further analysis of specific datasets reveals additional remarkable results. For instance, the 2016 dataset managed with only 18 features reached an accuracy of 96.1%, closely approximating the actual model performance. In 2017, both MOQBHHO and BMOCO achieved excellent results, but BMOCO’s 99.7% accuracy with 41 features stands out, showcasing its efficiency in feature reduction without compromising accuracy.

As discussed in the study, the Crowding Distance (CD) metric has been employed as the primary criterion for selecting the best non-dominated solutions at the end of an optimization process. This metric helps identify the most effective solutions that balance multiple objectives without bias, ensuring a fair comparison across all methods. Table 4 summarizes the best solutions selected based on the CD criterion, underscoring the superior performance of BMOCO in achieving high accuracy with fewer features across multiple datasets.

The detailed analysis of solutions presented in Table 4 highlights BMOCO’s exceptional ability to minimize the number of features while maximizing classification accuracy. For example, in the 2019 and 2020 datasets, BMOCO achieves nearly the highest accuracy with significantly fewer features than other methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in feature optimization and model efficiency. This performance indicates BMOCO’s robust strategy formulation and adaptation to the complexities of high-dimensional feature spaces. These results substantiate the potential of BMOCO in improving feature selection methodologies in complex, data-driven fields.

3.2. Performance Comparison based on Objective Function Metrics

It evaluates the performance of Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) compared to other benchmark methods based on objective function metrics, average feature size, and classification accuracy. These metrics provide insights into each method’s efficiency in reducing feature set dimensionality while maintaining or improving the model’s predictive accuracy.

Table 5 presents a detailed analysis of the average feature sizes and classification accuracy values obtained after 30 iterations of feature selection. Notably, BMOCO consistently achieves lower average feature sizes while maintaining competitive classification accuracies, emphasizing its efficiency in simplifying models without significant loss in performance. For instance, in the 2016 and 2020 datasets, BMOCO significantly reduces the number of features while achieving the highest classification accuracy among the compared methods. Additionally, in 2017, NSGA-II identified a more significant feature subset and achieved slightly higher accuracy than BMOCO, highlighting a trade-off between feature reduction and accuracy. However, BMOCO achieves near-optimal accuracy with considerably fewer features across all datasets, illustrating a substantial improvement in balancing model complexity and performance.

3.3. Performance Comparison based on Multi-objective Performance Measures

It assesses the efficacy of Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) relative to other established multi-objective feature selection algorithms. The evaluation is grounded on four critical performance metrics: Generational Distance (GD), Inverted Generational Distance (IGD), Hypervolume (HV), and Spread, which collectively offer a comprehensive view of each method’s capability to handle trade-offs between conflicting objectives effectively.

Analysis from Table 6 summarizes that BMOCO demonstrates superior or competitive performance across multiple datasets. Notably, BMOCO consistently exhibits the lowest GD and IGD values for the 2016, 2018, and 2019 datasets, suggesting a closer approximation to the actual Pareto fronts than other methods. Furthermore, BMOCO’s spread values are exceptionally high, indicating a comprehensive coverage across the objective space, which is essential for effectively exploring diverse solutions. For instance, in the 2022 dataset, BMOCO reached the highest spread of 1.03, significantly outperforming other methods for exploring extensive regions of the solution space. Additionally, the HV values of BMOCO are commendable, with consistently high marks, underscoring its ability to maintain a balance between convergence and diversity in solution quality.

3.4. Performance Comparison based on the Wilcoxon Signed-rank Test

Our study assesses the statistical significance of the performance differences between the proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) Feature Selection (FS) approach and other benchmark methods. To ensure robustness in the comparisons, we employ the Wilcoxon signed-rank test on Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) values collected from 20 distinct runs of each method. This nonparametric test helps determine whether two related paired samples come from the same distribution, an essential aspect of verifying the statistical superiority or equivalence of the proposed method relative to others.

| Datasets | Methods | Average Feature Size | Average Classification Accuracy(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | MOGA-FS | 39 | 96.92 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 35.25 | 96.27 |

| 2016 | NSGA-II-FS | 46.33 | 97.3 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 34.66 | 96.46 |

| - | BMOCO | 30.5 | 97.93 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 42.25 | 97.92 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 37 | 99.17 |

| 2017 | NSGA-II-FS | 47.66 | 99.33 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 28.66 | 98.3 |

| - | BMOCO | 25.5 | 99.23 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 44.75 | 98.87 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 44.5 | 99.22 |

| 2018 | NSGA-II-FS | 47.66 | 99.5 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 42.5 | 99.6 |

| - | BMOCO | 22.6 | 98.82 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 48.75 | 98.9 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 45.25 | 99.32 |

| 2019 | NSGA-II-FS | 46 | 99.5 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 43.75 | 99.6 |

| - | BMOCO | 21.8 | 98.82 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 46 | 98.9 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 43 | 99.34 |

| 2020 | NSGA-II-FS | 46.33 | 99.33 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 39.2 | 99.15 |

| - | BMOCO | 24.25 | 99.3 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 41 | 98.95 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 44 | 99.47 |

| 2021 | NSGA-II-FS | 47 | 99.25 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 42.25 | 99.5 |

| - | BMOCO | 24.5 | 98.8 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 39 | 98.9 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 41 | 99.4 |

| 2022 | NSGA-II-FS | 47 | 99.25 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 40.33 | 99.56 |

| - | BMOCO | 22 | 98.5 |

| Datasets | Methods | GD | IGD | HV | Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.56 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.66 |

| 2016 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.31 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.75 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.62 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.52 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.59 |

| 2017 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.38 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.90 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.72 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.50 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.49 |

| 2018 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.38 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.65 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.72 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.38 |

| 2019 | NSGA-II-FS | 1.15 | 1.21 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.63 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.72 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.37 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.35 |

| 2020 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.42 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.57 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.72 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.43 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| 2021 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.41 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.38 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.82 |

| - | MOGA-FS | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.35 |

| - | MOALO-FS | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| 2022 | NSGA-II-FS | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.41 |

| - | MOQBHHO-FS | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.34 |

| - | BMOCO | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 1.03 |

As presented in Table 7, the Wilcoxon test results exhibit statistically significant superiority (’++’) of the BMOCO method over most of the compared methods across most datasets. Specifically, BMOCO consistently outperforms others in datasets ranging from 2016 to 2021, except for 2022, where MOGA-FS shows superior performance as indicated by the ’–’ in the significance column. These results provide substantial statistical evidence that BMOCO is generally more effective at optimizing the trade-off between feature reduction and classification accuracy. Table 7 also highlights instances (’==’) where the performance between methods is statistically equivalent, providing a nuanced view of the competitive landscape in multi-objective feature selection.

| BMOCO vs | MOGA-FS | MOALO-FS | NSGA-II-FS | MOQBHHO-FS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | p-value | signf | p-value | signf | p-value | signf | p-value | signf |

| 2016 | 3.651×10-4 | ++ | 6.453×10-7 | ++ | 2.098×10-3 | ++ | 6.712×10-2 | ++ |

| 2017 | 7.812×10-2 | ++ | 2.115×10-6 | ++ | 3.167×10-3 | ++ | 2.651×10-6 | ++ |

| 2018 | 1.128×10-3 | ++ | 2.026×10-2 | ++ | 6.712×10-5 | ++ | 3.185×10-4 | ++ |

| 2019 | 7.802×10-4 | ++ | 1.812×10-3 | ++ | 3.832×10-5 | ++ | 2.873×10-3 | ++ |

| 2020 | 5.231×10-2 | ++ | 0.082 | == | 3.724×10-3 | ++ | 0.078 | == |

| 2021 | 1.874×10-2 | ++ | 4.843×10-4 | ++ | 3.954×10-2 | ++ | 5.325×10-5 | ++ |

| 2022 | 4.161×10-3 | – | 1.000 | == | 5.143×10-3 | ++ | 2.901×10-5 | ++ |

| Datasets | BMOCO | MOGA | MOALO | NSGA-II | MOQBHHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 15.71 | 21.25 | 23.18 | 27.37 | 16.92 |

| 2017 | 13.17 | 16.24 | 17.50 | 24.47 | 13.75 |

| 2018 | 13.05 | 15.21 | 15.33 | 25.67 | 14.09 |

| 2019 | 11.95 | 11.25 | 13.67 | 13.87 | 11.63 |

| 2020 | 10.21 | 13.52 | 14.07 | 19.39 | 11.25 |

| 2021 | 9.87 | 10.95 | 12.41 | 14.07 | 10.02 |

| 2022 | 8.32 | 10.28 | 13.35 | 13.35 | 7.85 |

3.5. Performance Evaluation based on Execution Time

This evaluation assesses the computational efficiency of five multi-objective Feature Selection (FS) methods by analyzing the average execution times across seven datasets. The proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization Algorithm (BMOCO) demonstrates superior performance due to its selective participation mechanism in the evolutionary process and dynamic adjustment between exploration and exploitation phases based on heuristic cues.

Table 8 presents that BMOCO often requires less time to complete its iterations than its counterparts. This is particularly notable in complex datasets where efficient execution is critical. The NSGA-II method, known for its rigorous merging of populations and generation of non-dominated fronts, consistently shows longer execution times. In contrast, BMOCO efficiently leverages its adaptive exploration and exploitation phases, reducing overall computational overhead. MOQBHHO also shows competitive execution times, benefiting from a similar mechanism that adjusts based on the situational needs of the algorithm. The results underscore BMOCO’s potential in applications where execution time and solution quality are paramount.

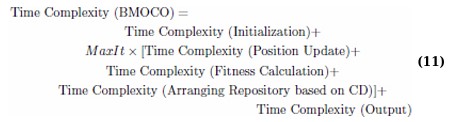

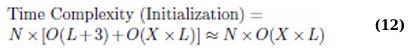

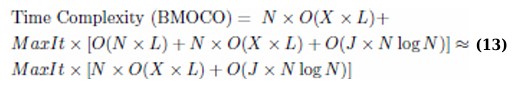

3.6. Computational Complexity Analysis

The computational complexity of the proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) used for feature selection in a K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) classifier framework is determined by several parameters: number of training samples (X), maximum number of iterations (MaxIt), population size (N), number of objective functions (J), and feature dimension (L). The total computational complexity of the BMOCO algorithm is represented by the following equation: (Eq. 11)

The computational effort required for initialization and each fitness calculation, when X training samples are involved, primarily depends on these parameters: the dimension of the features and the number of bits for the transfer function selection (L + 3). Typically, the complexity of fitness calculation using a KNN classifier is O(X × L). Thus, the initialization complexity is approximated by the following equation: (Eq. 12)

Each iteration involves updating positions, calculating fitness, and rearranging the repository based on crowding distance, which is computed by O(J × N log N) [17], considering N potential solutions and J objective functions that must be sorted as represented by the following equation: (Eq. 13)

This analysis underlines the BMOCO’s efficiency, especially in handling high-dimensional data through evolutionary operations and intelligent exploitation of feature space, resulting in a time complexity of approximately O(N log N).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Analysis of Selected Features

The analysis of features selected from various datasets highlights several critical determinants of infant survival: maternal education, prenatal care, pre-existing maternal conditions such as diabetes, maternal smoking during pregnancy, maternal Body Mass Index (BMI), infant birth weight, and breastfeeding practices. These factors collectively contribute to the varying rates of infant mortality observed across different socio-economic and demographic groups.

4.1.1. Maternal Education

Improved maternal education has been strongly associated with lower infant mortality rates. Higher levels of education among mothers often correlate with better economic status and access to healthcare resources, thereby enhancing the quality of prenatal and postnatal care. Studies have shown that infants born to well-educated mothers exhibit higher survival rates due to better healthcare practices and increased awareness of health-promoting behaviours [48].

4.1.2. Prenatal Care

Frequent and effective prenatal visits are pivotal for identifying and managing potential complications during pregnancy, such as diabetes [49]. Prenatal care includes routine check-ups, gestational diabetes management, and counselling, which significantly reduce risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth.

4.1.3. Diabetes Before Pregnancy

Mothers with pre-existing diabetes have a higher risk of complications that can lead to increased infant mortality if not properly managed. Effective control of blood sugar levels during pregnancy minimizes risks such as macrosomia (large body size of babies) and congenital anomalies [50].

4.1.4. Smoking During Pregnancy

Smoking during pregnancy is detrimental to fetal development, often leading to reduced growth, preterm birth, and increased risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in infants. The presence of harmful substances like carbon monoxide in tobacco smoke significantly impairs fetal oxygen supply [51].

4.1.5. Maternal BMI

High maternal BMI is linked to various adverse outcomes, including preterm births, low birth weight, and complications during labour, which can escalate the risk of infant mortality. This association highlights the importance of nutritional management before and during pregnancy [52].

4.1.6. Infant Birth Weight

Low birth weight is a critical factor in infant mortality, often associated with developmental issues and infection vulnerability. Babies with low birth weight require immediate and intensive care to mitigate risks of severe health complications [9].

4.1.7. Breastfeeding

Initiating breastfeeding shortly after birth is crucial for infant survival. Breast milk provides essential nutrients and antibodies vital for immune development, protecting newborns from common infectious diseases [53].

These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of infant mortality, highlighting the interplay among biological, environmental, and socio-economic factors. The selected features from the datasets reflect the direct influences on infant health and emphasize some broader public health implications. Addressing these determinants through targeted health policies and education can significantly enhance infant survival rates globally.

4.2. Positive Aspects of the Proposed Feature-Selection Method

Evaluating the proposed Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) across various metrics and tests has revealed several advantages that make it a robust feature selection method for medical data analytics, particularly in infant health. These advantages underscore BMOCO’s capability to efficiently navigate the complex landscape of feature selection by leveraging its unique algorithmic strategies.

4.2.1. Optimal Trade-off in Fitness Assessment

BMOCO excels at finding the optimal trade-off between two critical fitness assessment criteria. This capability allows it to outperform existing multi-objective methods, making it particularly effective for identifying features that significantly impact infant health.

4.2.2. Effective Population Diversity Management

A key strength of BMOCO lies in its ability to manage population diversity effectively. It selects the best candidates from the repository using the crowding distance metric in each iteration, ensuring a wide variety of genetic material is maintained for subsequent generations.

4.2.3. Superior Classification Accuracy

By incorporating transfer function optimization, BMOCO achieves the best classification accuracy with the smallest feature size across all evaluated datasets. This demonstrates its effectiveness in optimizing feature sets for precise health data analysis.

4.2.4. Utilization of KNN Classifier

Using the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier as a wrapper supports robust classification and reduces computational costs compared to other methods. KNN’s simplicity and effectiveness enhance the overall efficiency of BMOCO in feature selection tasks.

4.2.5. Convergence Rate

BMOCO exhibits a higher convergence rate than other methods. This is evidenced by lower Generational Distance (GD) and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) values of its Pareto fronts, indicating a closer approximation to the actual Pareto front.

4.2.6. Comprehensive Coverage in Objective Space

The spread of BMOCO’s non-dominated solution set is significantly large across all datasets, indicating the most extensive coverage in the objective space, which is crucial for thoroughly exploring potential solutions.

4.2.7. Efficiency in Execution Time

As highlighted in Table 8, BMOCO consistently requires less execution time than other evaluated methods. This efficiency makes it suitable for large-scale and time-sensitive applications.

Combining these features makes BMOCO a highly effective tool for feature selection in medical data analytics, particularly in applications where reducing feature dimensionality without sacrificing accuracy is critical.

While the current study focused on comparisons with evolutionary multi-objective methods, future work will also include evaluations against conventional filter-based and embedded feature selection techniques to further benchmark the generalizability and efficiency of the proposed BMOCO framework.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

This study introduces the Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization (BMOCO) with an enhanced transfer function optimizer designed for feature selection tasks.

It has been applied to an extended U.S. infant birth and mortality dataset. The main adaptation involved optimizing eight additional transfer functions to suit the binary nature of the feature selection problem. The proposed BMOCO algorithm was evaluated for its ability to reduce feature dimensions and its effectiveness in classification accuracy using the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier.

Compared to established multi-objective optimization methods such as MOGA, MOALO, NSGA-II, and MOQBHHO, BMOCO demonstrated superior performance in reducing feature count while enhancing classification accuracy. This was quantitatively supported by evaluating the quality of the Pareto fronts generated by BMOCO, which exhibited higher quality metrics across various performance indicators. BMOCO’s stability and efficacy were further validated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test on multiple runs’ Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) values.

The significance of BMOCO’s findings for biology and public health is further reinforced by the analysis of the selected features. Key determinants of infant survival, such as maternal education, prenatal care, pre-existing diabetes, maternal smoking, Body Mass Index (BMI), infant birth weight, and breastfeeding practices, were consistently identified, aligning closely with established clinical evidence. This convergence between computational outcomes and biomedical understanding highlights the practical value of the proposed method. By effectively surfacing medically validated risk factors, BMOCO demonstrates its potential as a reliable tool for guiding healthcare decision-making and informing targeted intervention strategies.

Despite its strengths, the current solution selection process in BMOCO relies solely on crowding distance, which, while effective, may be sensitive to the distribution of solutions and potentially overlook knee points, solutions that represent optimal trade-offs between objectives. Future work could incorporate knee-point detection strategies to better guide the selection of solutions that offer meaningful compromises. Additionally, BMOCO’s framework could be expanded to address more complex multi-objective problems by incorporating objectives related to feature relevance (e.g., correlation, mutual information), scalability, and computational efficiency. The applicability of BMOCO also extends beyond feature selection; future research could explore its adaptation to other binary optimization problems across domains [54].

Although our preprocessing steps include normalization to address scaling issues, the current version of BMOCO has not been explicitly evaluated under conditions of noisy, incomplete, or poor-quality data. This is a common challenge in real-world medical datasets and represents a limitation of the current study. In future work, we plan to assess the robustness of BMOCO by introducing synthetic noise and simulating missing values to better approximate real-world data imperfections and to evaluate the algorithm’s stability and resilience under such conditions.

It is also worth noting that the experimental analysis was primarily conducted on U.S. datasets, which may limit the generalizability of results across countries with varying healthcare infrastructures and socio-economic conditions. Therefore, future studies should investigate the algorithm’s performance using datasets from diverse regions and settings. Moreover, although BMOCO demonstrated robust performance on the current dataset, its behavior under noisy, incomplete, or imbalanced data, a frequent scenario in real-world clinical environments, was not extensively analyzed and warrants future investigation. While this study focused on wrapper-based optimization techniques, including comparisons with filter-based and embedded feature selection approaches could provide a more comprehensive view of the method’s relative strengths.

Finally, as MOQBHHO also yielded competitive results, future research could explore a hybridization of BMOCO with MOQBHHO to harness complementary strengths. Another promising direction is integrating filter-based methods into the BMOCO framework, introducing objectives such as correlation and mutual information. Such a hybrid filter-wrapper approach could enhance both the convergence speed and the robustness of the BMOCO algorithm in high-dimensional, noisy feature selection scenarios [55].

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: J.P., P.P.D., R.D., B.A., V.C.G., A.K., F.G.; data collection: J.P., P.P.D., R.D., B.A., V.C.G., A.K.; data analysis or interpretation: J.P., P.P.D., R.D., B.A., V.C.G., A.K.; methodology, investigation: J.P., P.P.D., R.D., B.A., V.C.G., A.K., F.G.; draft manuscript preparation: J.P., P.P.D., R.D., B.A., V.C.G., A.K., F.G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| BMOCO | = Binary Multi-Objective Cheetah Optimization |

| COA | = Cheetah Optimization Algorithm |

| CD | = Crowding Distance |

| FS | = Feature Selection |

| GD | = Generational Distance |

| HV | = Hypervolume |

| IGD | = Inverted Generational Distance |

| IMR | = Infant Mortality Rate |

| KNN | = K-Nearest Neighbors |

| MOGA-FS | = Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Feature Selection |

| MOALO-FS | = Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimizer for Feature Selection |

| MOQBHHO-FS | = Multi-Objective Quadratic Binary Harris Hawk Optimization for Feature Selection |

| MOO | = Multi-Objective Optimization |

| NICU | = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| NSGA-II-FS | = Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II for Feature Selection |

| S-shaped TF | = S-shaped Transfer Function |

| V-shaped TF | = V-shaped Transfer Function |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.