All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Systematic Evaluation of Telehealth using Recent COVID-19 Data

Abstract

Background:

The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) epidemic is a global public health issue. The COVID-19 outbreak can be managed with the help of telehealth. This systematic review sought to determine the role that telehealth services played in the COVID-19 epidemic in terms of disease management, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Methods:

Five databases were searched for this systematic review: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. As of December 31st, 2019, all published papers were written in English and appeared in peer-reviewed journals. These studies precisely described any use of telehealth services in all facets of healthcare during the COVID-19 outbreak. The quality of included studies was reviewed by two independent reviewers, who also gathered information and examined the search results. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) criteria were used to evaluate quality. The results were compiled into a narrative synthesis and reported.

Results:

Of the 142 search results, eight studies were pertinent for inclusion. Currently, telemedicine is, without a doubt, suitable for reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission among separated medical staff and patients. This approach might be used to reduce any direct physical contact, offer ongoing care to the neighbourhood and ultimately reduce the COVID-19 epidemic's morbidity and mortality rates.

Conclusion:

Telehealth enhances the delivery of healthcare services. In order to provide care during the COVID-19 outbreak while ensuring the safety of both patients and medical personnel, telemedicine should be a crucial tool.

1. BACKGROUND

A viral genus called Coronaviridae has been linked to diseases in both humans and animals [1, 2]. Human respiratory illnesses, ranging from the common cold to life-threatening conditions, have been linked to a number of coronaviruses. One source claims that coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) is caused due to the most recent coronavirus. The illness first manifested in Wuhan, China, and has since quickly spread worldwide [3]. Fever, dry cough, breathing problems, and dullness are some of the signs of COVID-19 [4, 5]. The disease's most severe form is more likely to develop in those over 65 and people with underlying medical conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart issues [1]. A genus of diseases called Coronaviridae can infect both humans and animals with disease. This global outbreak has been labelled a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) [6]. A key element in reducing viral transmission is the “social gap” or social distance that is brought about by decreased personal connection [7, 8]. Most cities have been quarantined, and travel restrictions have been enacted and enforced globally to prevent spread [9]. Conversely, those who do not have COVID-19 infection should receive daily care without the danger of sharing surfaces with hospital patients, especially those who are more likely to contract the illness (such as the elderly and those with underlying conditions) [7].

Furthermore, as part of strict infection control, clinical psychiatrists and other unnecessary staff are severely discouraged from entering the ward of a COVID-19 patient [10, 11]. There are numerous ways in which illnesses and natural catastrophes restrict access to healthcare [12]. In order to address the urgent medical requirements of COVID-19 patients, together with other patients in need of medical care, novel and creative solutions are required. More options are now available because of technological advancements [13]. The overall COVID-19 solution, despite the fact that it will consist of numerous components, is one of the greatest methods to employ modern technology to support the best service delivery while reducing the risk of direct person-to-person exposure [7, 14]. Telemedicine has the potential to enhance patient care, illness prevention, and epidemiological research.

A patient-centered 21st-century tactic, telehealth technology, safeguards patients, medical professionals, and other parties [15, 16]. Healthcare providers offer telehealth services when distance is a problem by using information and communication technology (ICT) to send credible information [17]. Real-time or store-and-forward distribution systems are used to provide telehealth services [18]. Most homes now have at least one digital device due to the rapid growth and size reduction of portable electronics, including smartphones [19] and webcams that connect patients and healthcare providers [20]. To lessen the risk of exposure to bystanders and personnel, healthcare programs are also provided to patients at high risk or those under quarantine via video conferencing and related technology. These systems allow doctors under quarantine to remotely treat their patients [8, 21]. Moreover, a tele-physician who serves multiple locations can help with various workforce-related issues [8, 22]. Particularly in non-emergency / regular care situations and those when direct patient-provider engagement is not necessary, such as when giving mental counselling, telehealth technology has many benefits [23]. Remote care increases access to care while using fewer resources in medical facilities and reducing the risk of potentially pathogenic transmission from one person to another [24]. Everyone's safety benefits from having widespread access to carers, including healthcare professionals, patients, and the general public [12]. This makes the technology appealing, useful, and affordable [14, 25, 26]. Patients are eager to adopt telemedicine despite the difficulties [27, 28]. The difficulties in putting these techniques into practise are also very dependent on accreditation, payment systems, and insurance (8). Moreover, some physicians worry about accountability, privacy, and security [22, 29].

While people are isolated, telehealth may be required for the general public, medical professionals, and COVID-19 patients. This makes it possible for people to get immediate professional medical advice. Determining and assessing the function of telehealth services in preventive medicine, diagnostics, treatment, and containment during the COVID-19 pandemic are the main objectives of this study. Telemedicine has emerged as a significant contributor to various facets of healthcare, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare professionals worldwide have extensively utilized telemedicine to facilitate remote consultations, enabling specialists to diagnose diseases through video conferencing and share knowledge for the treatment of COVID-19 without exposing themselves or others to the risk of infection. The utilization of telemedicine technologies, such as video conferencing, IoT-based remote monitoring, and mobile health apps, has allowed healthcare providers to conduct remote consultations, monitor patients' health, and provide ongoing care for those with chronic conditions. Telemedicine has also played a pivotal role in the swift implementation of COVID-19 screening and testing services, ensuring patients receive timely diagnosis and treatment.

Overall, telemedicine has demonstrated its immense value as a critical diagnostic tool for delivering healthcare services during the pandemic and beyond. Consequently, its importance has increased, drawing significant interest in investment and advancement to further enhance its capabilities. Telemedicine is poised to continue playing a crucial role in the future of healthcare delivery.

2. METHODS

2.1. Research Plan

Notwithstanding its drawbacks, telemedicine is enthusiastically accepted by patients [27, 28]. Insurance, payment methods, and accreditation have a significant role in the challenges of implementing these strategies [8]. Several medical professionals are also worried about the accountability, privacy, and safety of their patients [22, 29]. Telehealth may become essential for the general public, medical professionals, and COVID-19 patients as individuals continue to live in isolation. Now, patients can get immediate medical advice from a professional. Determining and evaluating the utility of telehealth services in preventing diseases, diagnosis, therapy, and management during the COVID-19 outbreak are the main goals of this study.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Methodology

To find pertinent and published publications, search terms were entered into five online databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. Searches were conducted in the database with a focus on Titles and Abstracts. A thorough investigation of the function of telehealth services during the 2019 new coronavirus outbreak was carried out on March 26th, 2020, and the results of this investigation produced a variety of available evidence. On April 3rd, 2020, a second search was conducted to update the results. The following keywords were used as search terms: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Novel Coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, Wuhan Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, SARS2, Tele*, Telemedicine, Tele-medicine, Telehealth, Telecare, Mobile Health, mHealth, Electronic health, and eHealth. The Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT were utilised to combine terms. During this stage, a librarian was consulted to confirm the search strategy. The search in each database was changed as a result. With the PubMed database, for instance, the following search methodology was required: “Coronavirus” [title] “abstract” OR “title/abstract” brand-new coronavirus 2019-nCoV or Wu-han coronavirus [title/abstract] [title/abstract]. For another option, SARS-CoV-2 [title/abstract] or SARS2 [title/abstract] were used. Apart from that, (Telemedicine [title/abstract] OR [title/abstract] Telemedicine OR [title/abstract] Tel- ehealth OR [title/abstract] OR [title/abstract] Telehealth OR [title/abstract] Telecare [Title/Abstract] OR mobile health ([title/abstract] OR Electronic health) mHealth OR eHealth were used. For manual searches in online resources, Google, Google Scholar, journals that published important articles, and specific websites (WHO, https://www.who.int, CDC, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, https://www.nice.org.uk) were used. In addition, we searched the chosen publications' references for any new information that the initial searches might overlook (reference by reference).

2.3. Eligibility Requirements

We considered all papers that had information on how telehealth services affected COVID-19 in our study. Between December 31st, 2019, and April 3rd, 2020, peer-reviewed studies that were published in English and demonstrated the use of telehealth in the prophylaxis, diagnosis, management, and treatment of COVID-19 were included. December 31st was selected since it falls on the same day as COVID-19's arrival in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. In fact, every research demonstrating the use of telehealth technology in any area of healthcare (primary, secondary, or tertiary) was included. This included clinical services, such as diagnosis, symptom assessment, patient triage, consultation services, clinical supervision, and training programmes. Studies that provided insufficient data, duplicate publications, review papers, opinion pieces, and letters, as well as research on other technologies (including the Internet of Medical Things, or IoMT), were also deleted.

2.4. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Two authors, in addition to conducting the literature search, independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria and evaluated the studies based on their titles and abstracts [30]. The full texts of studies were obtained and analysed after a preliminary screening to determine their appropriateness for the construction of a table for data extraction. Data were collected from all papers that complied with the review's eligibility and inclusion requirements. The following information was gathered and analysed: first author, publication date, nation, study design, type of telehealth employed, significant study findings, and telehealth impacts.

2.5. Quality Evaluation

Checklists from the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) were used to rate the included studies' level of quality. People can learn how to critically examine evidence using the CASP tools [31]. To evaluate the included studies' quality, they were split into three categories: poor, average, and excellent.

2.6. Evidence Integration

A narrative synthesis of the entire body of evidence was produced by comparing and contrasting the data in order to convey and summarize the findings of the included research. A preliminary synthesis was performed, links between and within the research were examined, and the robustness of the synthesis was evaluated as the first of the three stages of narrative synthesis [32]. The data from the included research were qualitatively presented and reported. The writers frequently discussed the outcomes in order to get to a consensus.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search Outcomes

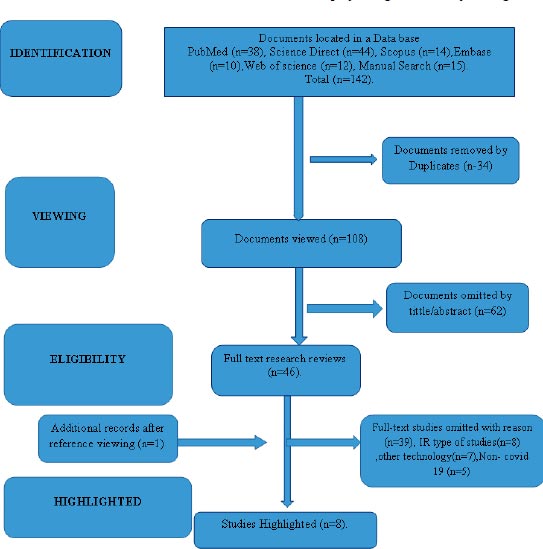

Fig. (1) depicts the characteristics of the screening and literature review procedures. After eliminating duplicate search results and reviewing study titles and abstracts, we selected 46 pertinent full-text studies. Due to their failure to meet our admissions requirements, 39 of the remaining studies were excluded. After reference screening (reference by reference), eight full studies were included, and one additional study was added.

3.2. The Characteristics of Included Studies

The characteristics of the studies that were taken into consideration are mentioned in Table 1. The majority of the studies featured and published in different international journals between February 17th, 2020 and April 9th, 2020 were carried out in the United States. Eight studies were considered, each with a n of 1, and conducted in one of the following six nations: Iran (n=1), Italy (n=1), the United States (n=5), China (n=2), the United Kingdom (n=2), Canada (n=2), and the United States (n=2). Five cross-sectional studies, two case studies, and one case-control study were included in the study. During the COVID-19 epidemic, the majority of telehealth and social media platforms, including the phone, live teleconferencing, and email, were utilized.

| Author /Date | Country | Design of Study | Type of Tele -health | Key Outputs | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davar Panah et al. 17/02/2020(33) |

Iran | Case Study | Social Networking Sites Platform with Email, Whatsapp and Chats Apps | -Quicker Delivery Of Teleradiology Services from a Teleradiology opinion Group - Create a coordinator for the volunteer Network (Humanitarian) - Covid -19 Infection Triage Employing Radiology Specialists from Global centers. |

-Made it necessary to transfer patients to overcrowded facilities. - Met the local need by providing near real-time advice from experts around the nation and the globe. -Satisfied a local need. - Offered advice in areas with limited access to thoracic, radiology expertise. - Might address the scarcity of on-site. -Thoracic radiologists established agreement among radiologists through online group discussions. |

| Zhoi et al./ 23/02/2020(34 ) |

China Uk Case Study | Mobile And Live Video Conferencing | -Offering rapid diagnosis & advice Covid -19 to Doctors & Patients. -Collecting transforming & evaluating Patient Health Data. -Wireless remote patient monitoring, Remote multi disciplinary treatment for different consultations for patient awareness. |

Direct physical contact was avoided; The potential transmission of infection to doctors & nurses was prevented. Real-time data exchange was achieved; Prevention & treatment guidelines were accessed; Guidance on drug use & management of corona-virus patients was obtained; Primary case guidance on corona virus for all was add listed by the specialists treatment team was achieved. |

|

| Reeves et al./ 24/03/2020(35) | USA | Cross Sectional | Message on Electronic Medical Record. | Offering discussion support to those in need of testing; training patients via phone calls; screening or treating patients in urgent core Settings; Repurposing & using an electronic medical record. Optimization team to train end user s video visit work flows & telemedicine-video visits for outpatient clinic encounters. | Addressing patients worries, reports regarding prior ongoing & upcoming tests training completion & screening, documentation compliance ,updated travel & symptoms Screening, testing creation & clear guidance. On the best setting & location of patient care; Clinical decision support on testing criteria standard reporting of any examination of patient visitors for infection symptoms sample letter of justification for professionals urging clients to work from home. |

| Nicol et al./ 24/03/2020(36) |

USA Canada | Cross Sectional | Use of social media or other digital tools, such as phone calls, emails & video conferences. | Providing electronic consultations or assistance to healthcare professionals; facilitating electronic informed consent, digital assessment tools & virtual study visits. | Reduced the usage of public transportation; Facilitated the implementation of social distancing could be used away from high-risk locations such as hospital grounds; Provided the necessary safeguards for human research protection; reduced mortality among these vulnerable people During the covid -19 pandemic; disseminated factual & understandable information at a time when older people & their families are inundated with conflicting & muddled messages. |

| Simcock et al./ 24/03/2020 (37) | UK, USA & Italy | Cross Sectional | Telephone, Video & Laptops. | Use in remote monitoring; video consultations; telephone follow-up in a variety of cancer situations, endometrial, prostate, lung, colorectal cancers. | Reduce infection risks also risks associated with work force ageing, reduced covid-19transmission risk during radiation treatment; facilitated access to the hospital data or treatment planning systems. |

| Greenhawt 26/03/2020(38). |

Usa Canada |

Cross Sectional |

Website, Patient Potal Messages, Digital Pictures, Video Using HIPAA Complaint Platform, Electronic Medical Record. | Delivering allergy services; phone triage as a visible option for allergic Rhaetia patients ; providing telehealth visits; follow up with patients who have utricoria, angiodem & atopic dermatitis via phone triage or telehealth adapting services for food allergy , eosinophilic esophagistis(eoe), drug allergy & anaphylaxis; adapting services for immune-deficiency; immunotherapy. | Reducing patient exposure & maintaining social distancing while providing access to the rapid evaluation for potential covid-19 infection. meeting healthcare needs. Aiding in the visualization of any rash. Limiting the exposure of healthcare personal to Potentially infected people. Options for virtual care to guarantee continuing of care was successful in managing Patients with long term conditions offered the channel to Integrate tele-health with an allergy practice less demand on the patients resources. |

| Cohen et al. 7/04/2022 (39) |

USA | Cross Sectional |

Skype, apple face time, face book messenger video chat & Mobile health technology are some of the apps available today. |

To create staffing plans, conduct appropriate telehealth visits, use in psychological treatments, communicate with the family, friends & coworkers including evaluate patients in person or via telemedicine if they are at high risk of infection (patients or location specific). |

Early treatment correlated with improved outcomes; Reduces hospital staff exposure to the patients & to themselves minimized unnecessary exposure to the patients. |

| Zhou et al. 09/04/2020 |

China | Case Control | Integrated Macro Micro Video Mode | The training video is being streamed live, video scan Be viewed repeatedly was used to train new nurses communication Skills. |

Higher satisfaction ,easier comprehension, Higher instructor assessment & harvest, real world Clinical experience & alleviation of the absence of clinical nursing teaching materials were all benefits. |

3.3. Quality Evaluation

Eight studies from our systematic review were evaluated using CASP methods. Six studies (or 75% of all studies) were of high quality, as opposed to two (or 25%) of medium quality. Also, no studies were disregarded based on the evaluation of their degree of quality.

3.4. Telehealth Services Amid the COVID-19 Outbreak

In-depth information on telehealth and the COVID-19 infection status may be found in eight studies. With the use of telehealth, several healthcare organizations and situations could be combined into a single virtual network under the management of the main clinic. This network may include actual physical locations, including outlying and central clinics, preventative centres, private clinics, private doctors' offices, and rehabilitation facilities, as well as all of the registered patients in those locations. We can free up the medical staff and resources required for patients who get dangerously ill with COVID-19 by deferring elective treatments or yearly exams in favor of adopting virtual care for extremely basic, vital medical care. By avoiding congregating in small spaces like waiting rooms, the coronavirus's propensity to transfer from one person to another can also be prevented. Keeping individuals at a distance is referred to as “social distance.” Medical distancing is the practice of separating medical staff from patients and other providers. Telehealth is one approach that we can adopt to achieve this practice. In order to reduce the workload on healthcare providers and the healthcare system, prevent the spread of disease, direct people to the appropriate level of care, ensure the security of providing health services online, and protect patients, clinicians, and the community from infection exposure, telehealth can mobilize all aspects of healthcare potential. Control and triage during the COVID-19 pandemic, self- and remote monitoring, therapy, patients after discharge in health centres (follow-ups), and use of online health services are a few examples of patient telehealth utilization scenarios. These methods might reduce pandemic-related morbidity and mortality rates. The ability to work remotely with patients who have mild symptoms, speed up access to medical decisions, get a second opinion for patients with severe cases, share cross-border experiences, and offer teleradiology and online training for healthcare professionals are still available to all clinicians and healthcare professionals. In order to retain access to essential healthcare, telehealth should be a significant weapon in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic study aimed to assess how telehealth services helped with disease management, diagnosis, and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. With the aim of enhancing COVID-19 infection management, we discussed the advantages and implications of several telehealth techniques in this review. Since there is currently no vaccine available anywhere in the globe to defend against COVID-19, the best preventive measure is to limit coronavirus exposure [33]. It is advised to use face masks when in crowded areas, use tissues for coughing and sneezing, regularly wash your hands with soap and water or hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol, maintain a true social distance from other people, avoid close contact, and refrain from touching your eyes, nose, or mouth with contaminated objects. Healthcare practitioners can connect with their patients through ICT tools for triaging, assessing, and caring for all patients, hence lowering the number of persons who need in-person medical services [24]. With the help of live video conferencing or a straightforward smartphone call, medical professionals can ask specific questions, gather relevant data, rank individuals for appointments, and determine whether a patient can continue to self-monitor symptoms at home while healing. It can also be used to measure things like blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and respiration rate on a regular basis at home [34]. Due to online mental health surveys and communication tools like Weibo, WeChat, and TikTok, medical authorities and mental health specialists have been able to provide safe web-based mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in China [35]. To assure the ongoing availability of mental health therapies and lower the risk of cross-infections, Chinese government authorities have established a remote consultation network that permits internet or telephone consultations in a secure setting [36]. Many free electronic publications and online suggestions regarding COVID-19 have also been made available by the National Health Commission of China in an effort to promote emergency interventions, increase safety, and raise their calibre and efficacy [10]. By easing the mental health burden of COVID-19 and disseminating knowledge about the signs of burnout, despair, and anxiety, telehealth can also offer mental online health therapies to isolated patients [14].According to Greenhawt et al., telemedicine has a number of advantages for treating allergy and immunology conditions, such as minimising the amount of time that medical staff requires to interact with patients who might be contagious and enabling quick COVID-19 infection testing [37]. The study discovered that during the tragic COVID-19 epidemic in Iran, a novel screening and triage strategy was utilised in addition to the conventional procedures for identifying COVID-19. The Iranian Society of Radiology (ISR) provided teleradiology and teleconsultation services using a social media platform to address the lack of on-site thoracic radiologists during the COVID-19 outbreak [38]. Staff members should use mobile health technology to create staffing plans and handle billing for healthcare services in addition to taking action to guarantee the health and safety of patients [39]. Our results showed a wide range of simple-to-set-up COVID-19 management options that provide live video consultation. Through the use of live video conferencing, individuals can help prevent direct physical contact, which lowers the risk of coming into touch with respiratory secretions and prevents the disease from spreading to medical workers [34]. In addition, live video may be useful for patients needing COVID-19 consultation, for nervous patients, and in place of in-person visits for assessments of chronic illnesses (such as diabetes and cancer), some medication checks, and triage when the telephone is not enough [22]. Video consultations and telephone follow-ups are practical in a variety of cancer situations, including lung, endometrial, colorectal, and prostate cancer [40], to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In ambulatory and urgent care settings, phone calls and electronic health records (EHR) can facilitate decision-making among healthcare team members and facilitate patient screening or treatment without the need for in-person visits, according to a study conducted in the USA [41]. Telemedicine is important during the pandemics, such as COVID-19, in terms of lowering morbidity and keeping the public away from high-risk locations like hospital grounds. Older people can use technology to access healthcare services [42]. Changes in payment and service coordination, along with successful local system adaptation, are now the key obstacles impeding the widespread use of telemedicine to treat COVID-19 infection (8). In our opinion, the COVID-19 pandemic can be averted and controlled by reconsidering traditional notions of clinical practice, utilizing secure online environments, and enhancing telehealth worker and patient education.

5. FUTURE INVESTIGATION

Future telehealth usage studies are anticipated to concentrate on figuring out the challenges and facilitators that patients and healthcare professionals encounter. Future research should examine how telemedicine choices affect hospital performance and efficiency measures. Further global study is required to identify how to integrate telehealth into primary care. Researchers can also examine the efficacy of telehealth approaches in different healthcare settings, especially in the area of home nursing for vulnerable elderly community members. The use of this technology in psychiatry is also strongly advised because it lessens the need for in-person sessions. Future studies can examine how satisfied patients and healthcare providers are with telehealth services. The integration of telemedicine with artificial intelligence is an ongoing process that has already been applied in various healthcare sectors. This integration aims to provide healthcare professionals with the means to make rapid and well-informed decisions in areas, such as disease diagnosis, treatment, and the selection of optimal parameters for medicine and surgery. The synergy between telemedicine and artificial intelligence holds great potential in improving quality of life and promoting overall health. It is clear that the future of healthcare lies in the advancement of telemedicine technology in conjunction with the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI).

6. LIMITATIONS

Our comprehensive review identified three limitations. Firstly, there is a possibility that certain influential studies published in languages other than English, such as Chinese, may have been inadvertently overlooked. Secondly, we did not have access to databases like CINAHL and PsycINFO, which could potentially contain relevant information. Thirdly, despite employing a rigorous search methodology and aiming to encompass a broad range of global evidence, it is conceivable that some additional research pertaining to this subject may have been inadvertently excluded from our analysis. Despite our best efforts, further studies likely exist in the literature that we could not incorporate into our review.

CONCLUSION

This study exclusively focused on delineating the benefits of telemedicine within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. It presented a comprehensive and systematic review investigating the efficacy of telehealth interventions during an unprecedented global health crisis. The primary objective of the study was to analyze the role played by telehealth in addressing the urgent research needs outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) pertaining to infection management and the dissemination of the latest information during the initial stages of the outbreak. The escalating global spread of COVID-19 has underscored the pressing deficiencies within the healthcare system, necessitating prompt action. Telehealth emerges as a potential solution to address several critical challenges encountered in the delivery of healthcare services amidst the pandemic. By leveraging telehealth technologies, the need for direct physical contact can be circumvented, thereby mitigating the risk of COVID-19 transmission while ensuring the uninterrupted provision of care to communities. The empirical findings derived from this comprehensive review strongly advocate for the adoption of telehealth tools by both patients and clinicians as a viable and effective strategy to prevent and contain the spread of COVID-19 infection. Moreover, the integration of telemedicine technology with artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the healthcare sector. It not only facilitates remote access to medical care and assists in pandemic management but also enhances decision-making capabilities, leading to more effective and precise diagnoses, treatments, and patient monitoring. One of the key advantages of telemedicine with AI is its ability to leverage machine learning algorithms to analyze vast amounts of patient data, enabling the identification of patterns that can be utilized to predict health outcomes. This empowers healthcare providers to make well-informed decisions regarding treatment plans and establish correlations between past medical history and diseases, ultimately resulting in enhanced patient care. In summary, telemedicine technology combined with AI has the capacity to reshape the healthcare industry, significantly improving the efficiency and accuracy of disease treatment.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CASP | = Critical Appraisal Skills Program |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| AI | = Artificial Intelligence |

| ISR | = Iranian Society of Radiology |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Salman Akthar is the associate editorial board member of the journal The Open Bioinformatics Journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.